The Sky Is the Limit: Reflections on the Vertical City

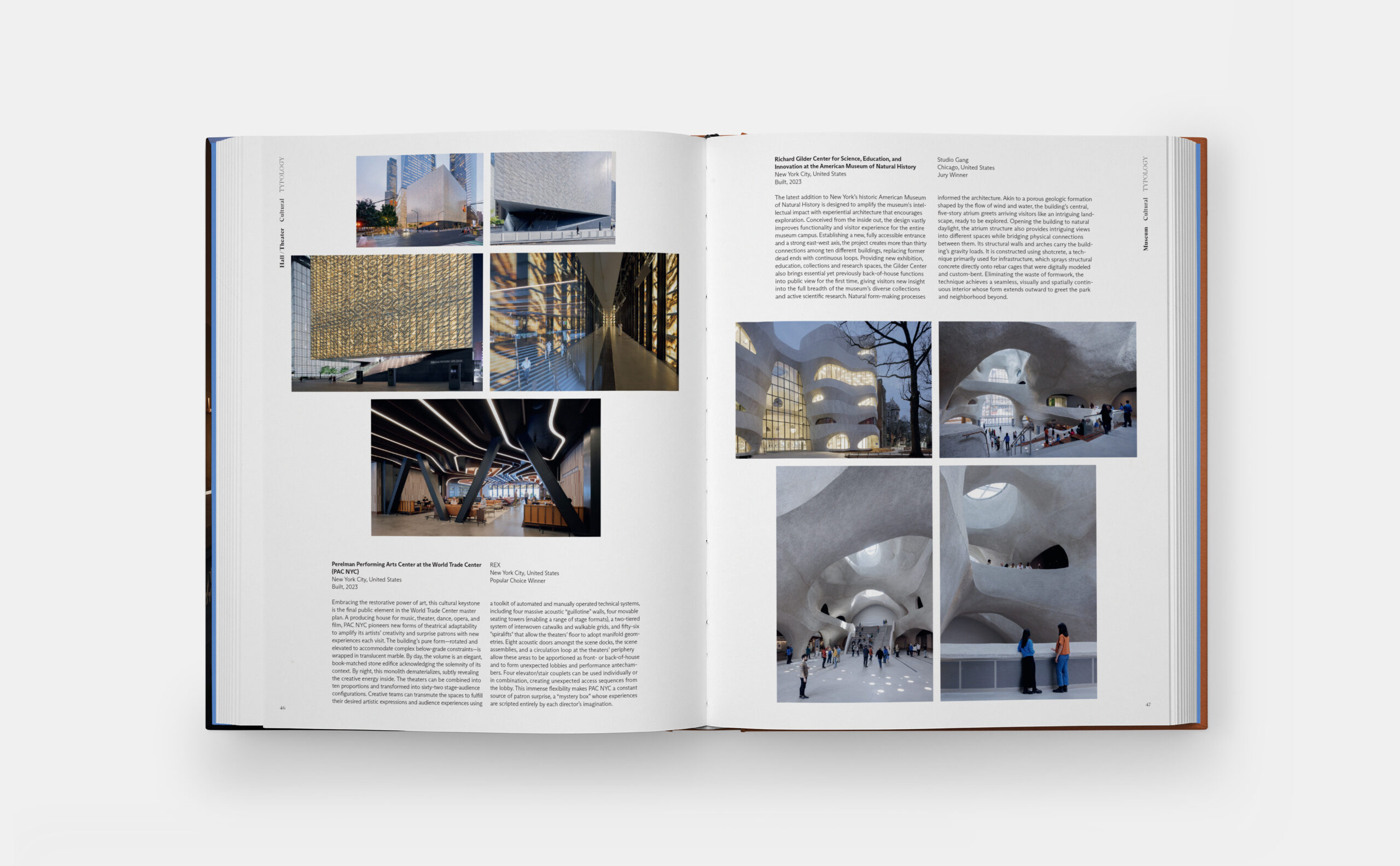

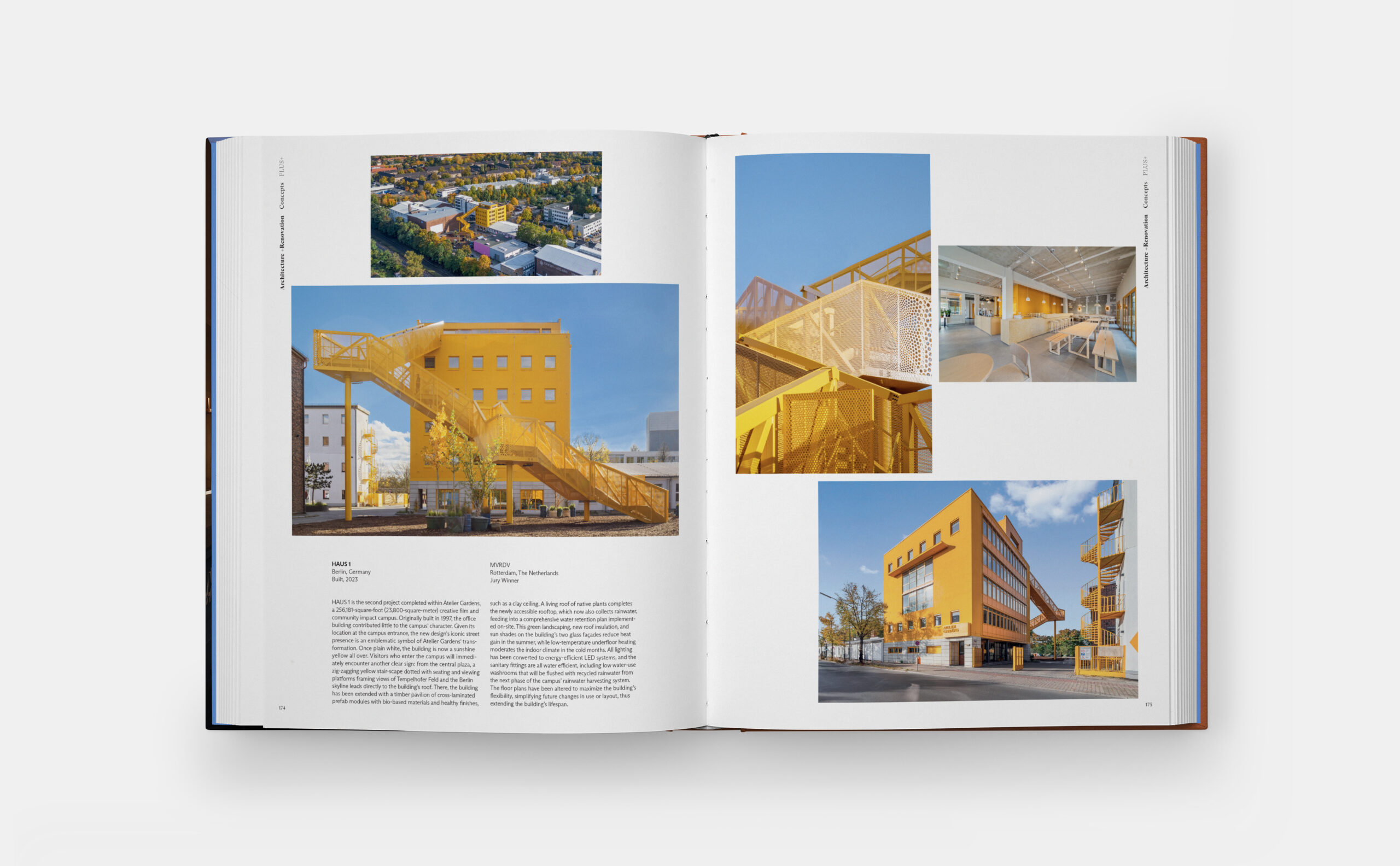

The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.

Once again, discussions on minimizing urban sprawl, over-population as well as the urgency for natural preservation, have brought the concept of the vertical city to the architectural foreground. Still, the term vertical city actually evades definition.

In the early 1900s, when skyscrapers gradually became the new norm in major cities such as New York and Chicago, people experienced a profound new way of living. Instead of commuting across the streets, they were moving vertically, through countless floors, to reach their home, workplace, or any other sort of entertainment. Examples such as the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building contributed to equating skyscrapers with a sense of architectural grandeur rather than a prelude to a more sustainable and perhaps conscious urban strategy.

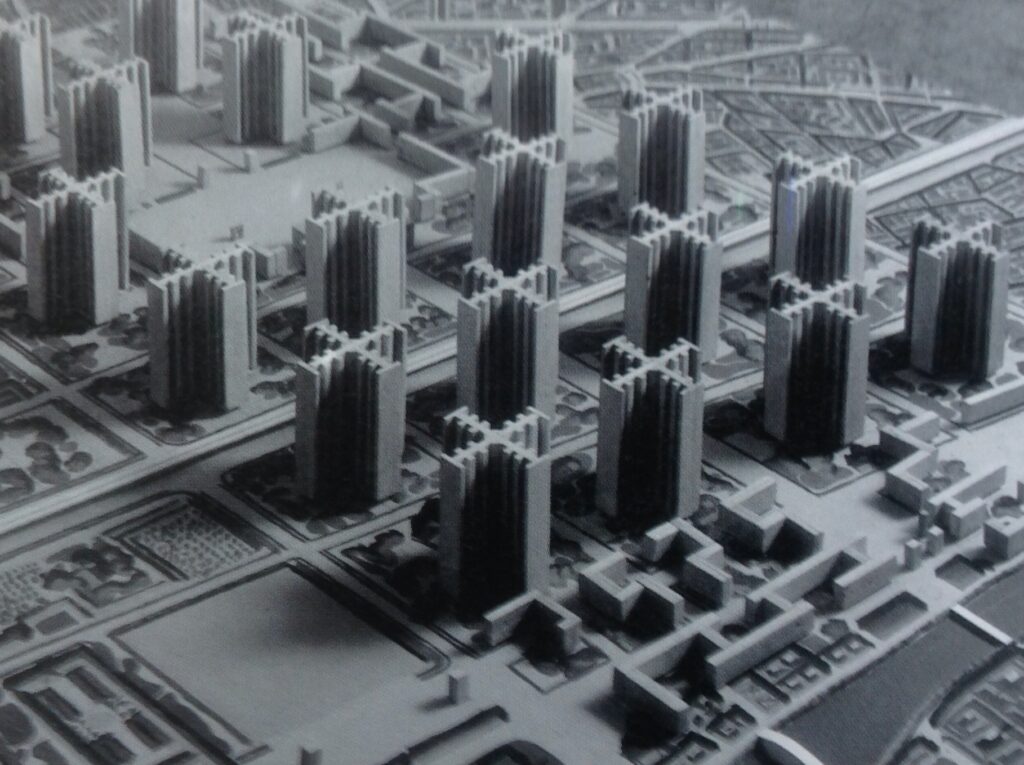

In parallel, many utopian visionaries have constructed their own unique versions, starting from alleged ancient wonders such as the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, to Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse, which suggests an austere urban organization of residences on top of the remnants of vernacular European cities. Additionally, other visionary projects include Friedrich St Florian’s Vertical City, a 5,250 feet tall (1,600 meters) cylindrical building located in the middle of a lake, reaching above the clouds and powered with solar energy, as well as MVRDV’s contemporary — and highly debated — Pig City, where vertical megastructures are designed as organic farms for the Netherlands that improve the livestock’s living conditions while eliminating the costs and pollution for transportation and distribution — i.e., a city as a central food-core.

Naturally, these projects are all advocating for a better future, whether it being a more communal cohabitation model, an environmentally sustainable solution or even a gateway to technological advancements in the construction industry. Still, a key observation in regard to this concept is that it is either presented as a distinct skyscraper (a singular vertical building) or a building archetype that is copied and repositioned in strict organizational grids (a cluster of vertical buildings) usually compressed in a small urban footprint. As a result, a paradoxical question arises: what is actually considered as a vertical city?

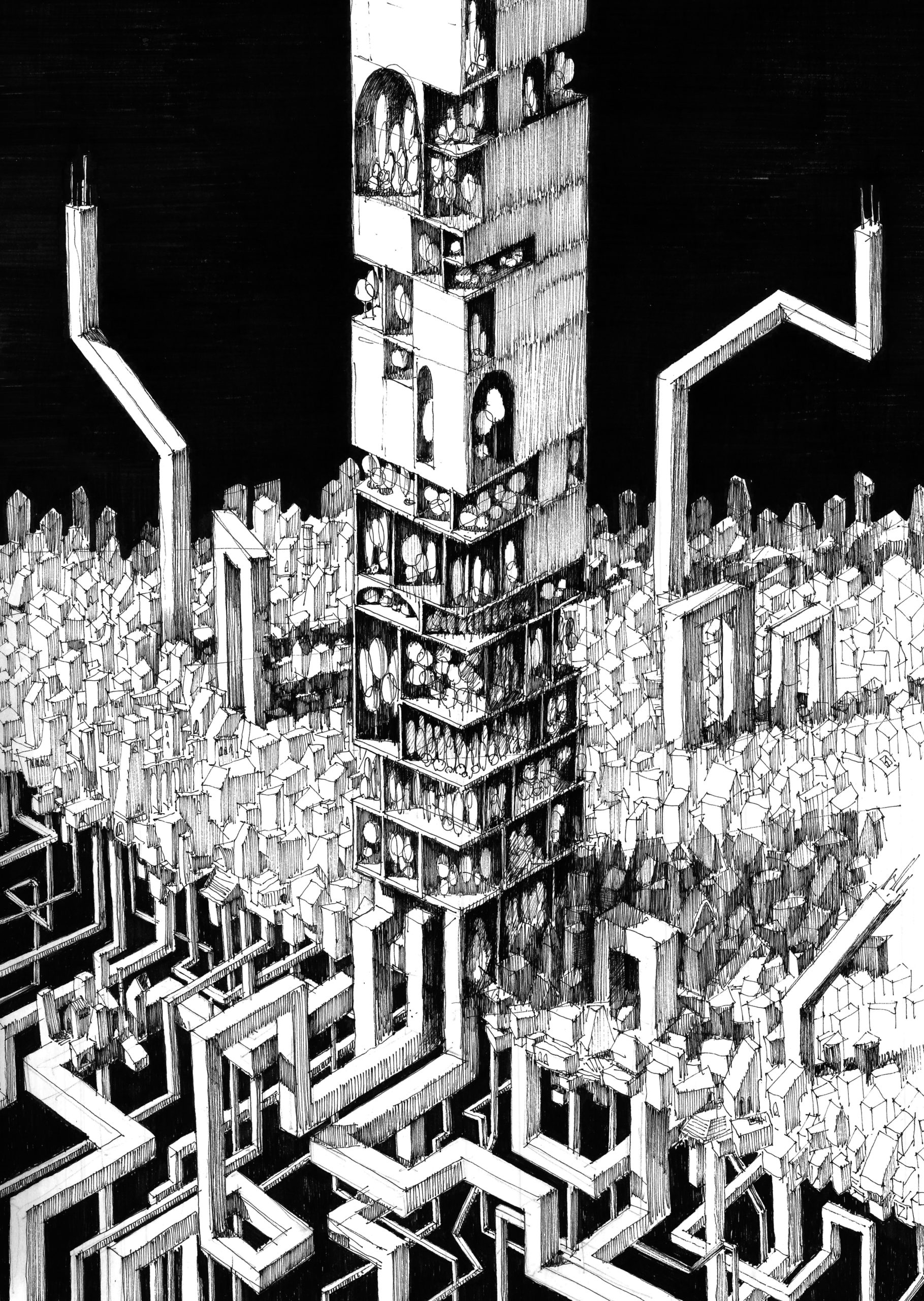

Imagining a Vertical Forest by Endrit Marku, The One Drawing Challenge 2022

To this day, a mixed-use skyscraper is (positively) viewed as such, creating an environment where people can carry on with their everyday lives without ever leaving their buildings. From residences to offices, sports facilities, entertainment floors, restaurants and bars, these 100-plus-floor structures turn into neighborhoods and communities that lack nothing (in terms of function) compared to those sprawling along the ground — except, perhaps, more fresh air.

Still, the idea of living solely in one giant megastructure is a close reminder of J.G. Ballard’s dystopian High Rise novel, which describes the disintegration of a luxury high-rise building where its residents gradually descend into chaos. On the other, is constructing an array of new, vertical structures — similar to those of the Pig City — even in smaller urban footprints a better strategy for dealing with the current overpopulation and environmental challenges our world faces? And, if yes, what happens to all these cities and buildings that are left behind? Perhaps the answer lies somewhere in the middle, in a scenario where less production offers more availability, and where a series of strategies propose a “vertical” future that is not only alluring but also plausible.

Footprint Exchange

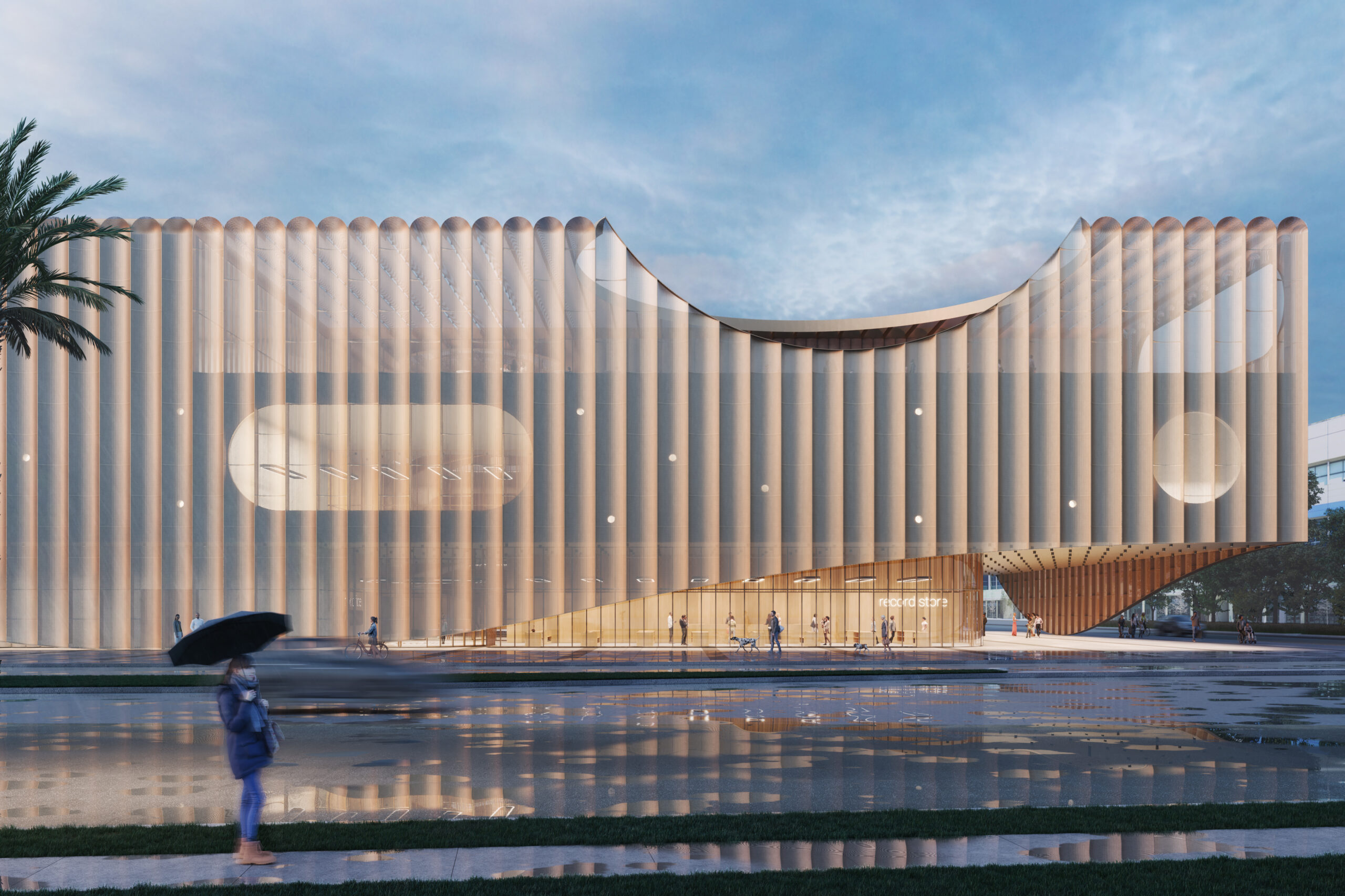

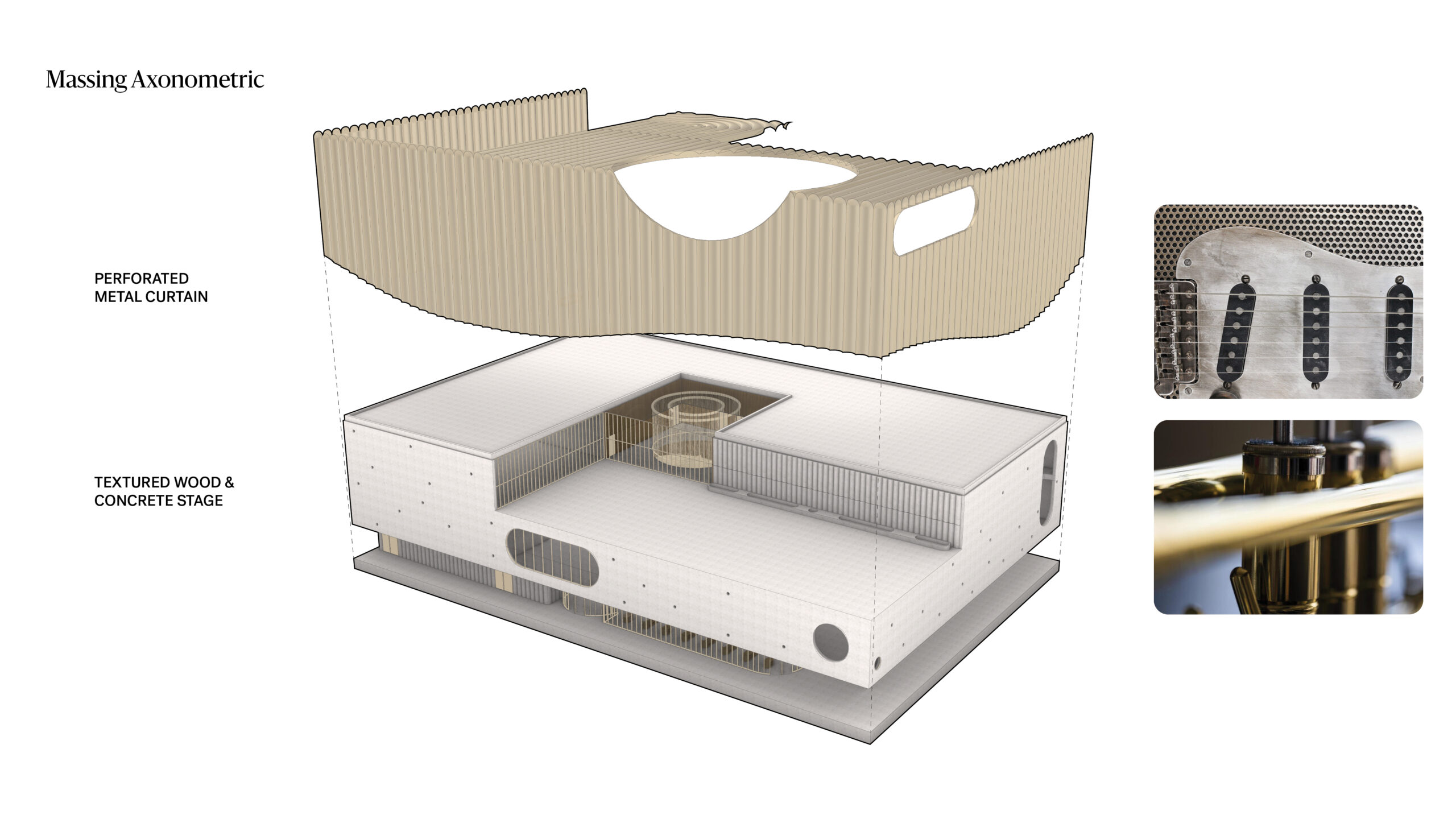

Vertical Cities by Luca Curci Architects, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

By setting up a trade between the erection of a vertical structure and the demolition of an existing low-rise block, would enable the inhabitants to relocate, without providing any incentive for increasing the area’s population and simultaneously making room for nature to reclaim large parts of the ground. At the same time, parts of cultural heritage, such as historic sites, cultural buildings and local neighborhoods will be preserved, thus motivating the residents to once in a while “escape their skyscraper” and keep ties with the people that choose to stay on the ground.

Vertical City vs. Vertical Island

Imagine a single building in the middle of lush mountains, rivers and greenery, without any other form of human settlement nearby — i.e., a vertical city. Now, imagine a hybrid cluster of such structures amongst preserved pieces of existing cities along with an abundance of natural parks, forests and water — i.e., a vertical island. To avoid any other additional dystopian visions, perhaps it is best to seek ways to construct vertical islands rather than cities. More specifically, islands are self-sufficient places that encourage diverse cohabitation and interaction between communities; in other words, albeit solitary and independent, they are far from uniform and unchanging.

Vertical Infrastructure

Finally, establishing the infrastructure to connect these vertical islands, both within their urban fabric and with neighboring structures, is crucial for preserving cultural diversity, fostering communication, and supporting globalization, all while minimizing land use. Whether this takes the form of overground trains, helicopter pads or flying cars, transportation works that conquer the forces of gravity will play a major role in island-cities.

The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.

Featured Image: Vertical Life by Xi Xi Chen, One Photo Challenge 2022

The post The Sky Is the Limit: Reflections on the Vertical City appeared first on Journal.

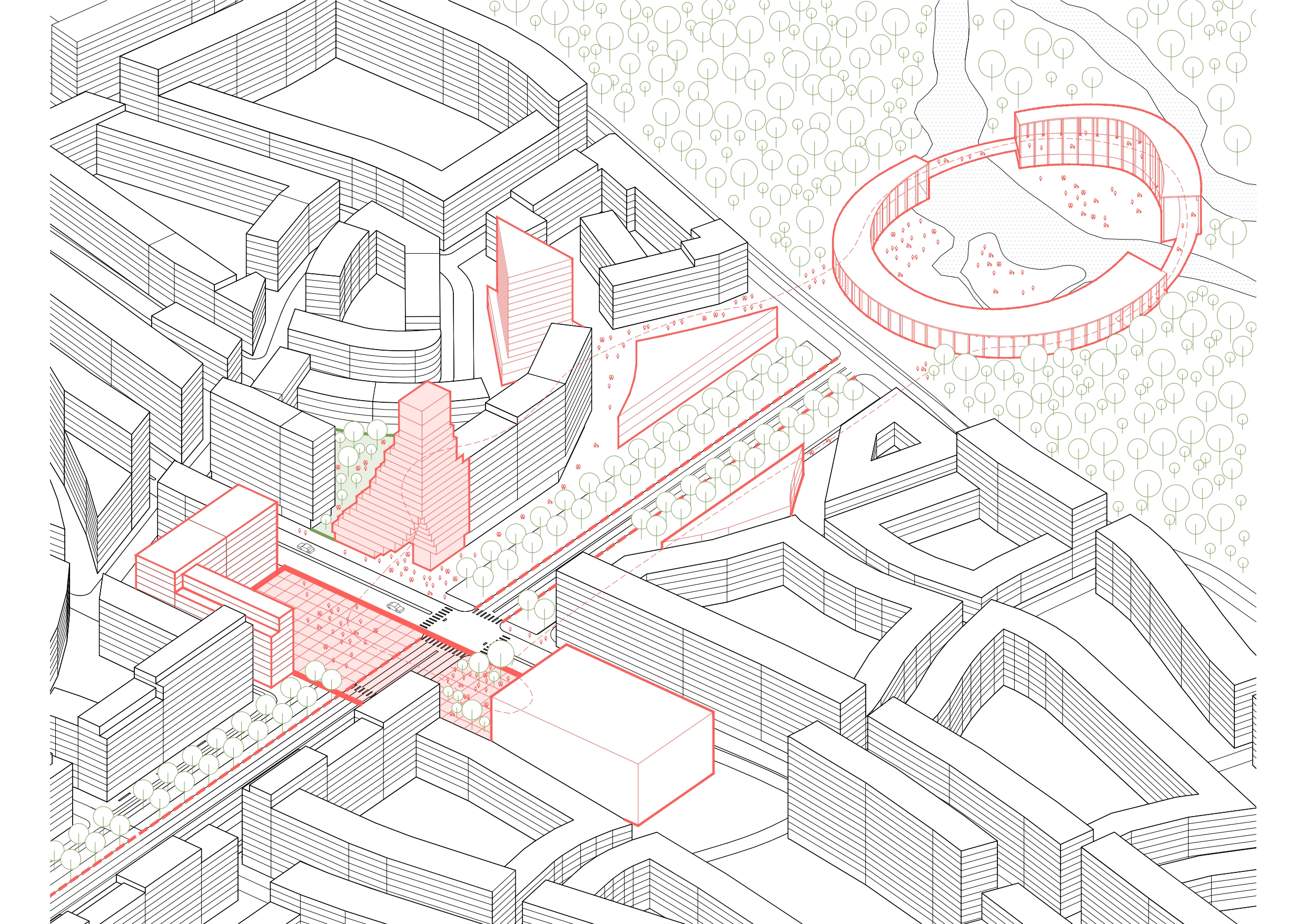

Mount Tirana will be the tallest building in Albania at 185 meters, drawing inspiration from the country’s mountainous landscape. Located in central Tirana near the National Historical Museum, the project reflects Albania’s cultural heritage and natural surroundings. The tower will feature housing, commercial spaces, a boutique hotel, offices and restaurants. Its design incorporates terraces with local plants to reduce the need for cooling, while the use of locally sourced materials, like natural stone, minimizes the building’s carbon footprint.

Mount Tirana will be the tallest building in Albania at 185 meters, drawing inspiration from the country’s mountainous landscape. Located in central Tirana near the National Historical Museum, the project reflects Albania’s cultural heritage and natural surroundings. The tower will feature housing, commercial spaces, a boutique hotel, offices and restaurants. Its design incorporates terraces with local plants to reduce the need for cooling, while the use of locally sourced materials, like natural stone, minimizes the building’s carbon footprint.

Once a monument built to honor dictator Enver Hoxha, The Pyramid of Tirana has been dramatically transformed by MVRDV into a vibrant cultural hub. Originally a brutalist museum, the deteriorating structure has been repurposed into a space that serves Albania’s youth and cultural life.

Once a monument built to honor dictator Enver Hoxha, The Pyramid of Tirana has been dramatically transformed by MVRDV into a vibrant cultural hub. Originally a brutalist museum, the deteriorating structure has been repurposed into a space that serves Albania’s youth and cultural life.

Hora Vertikale is a new residential project in Tirana that reimagines urban living through a vertical settlement inspired by the ancient Albanian “Hora.” The development features a series of towers designed as a vertical village, set amidst a green park. Sustainability is at the core of the project, with locally sourced materials used to minimize the carbon footprint and support the local economy.

Hora Vertikale is a new residential project in Tirana that reimagines urban living through a vertical settlement inspired by the ancient Albanian “Hora.” The development features a series of towers designed as a vertical village, set amidst a green park. Sustainability is at the core of the project, with locally sourced materials used to minimize the carbon footprint and support the local economy.

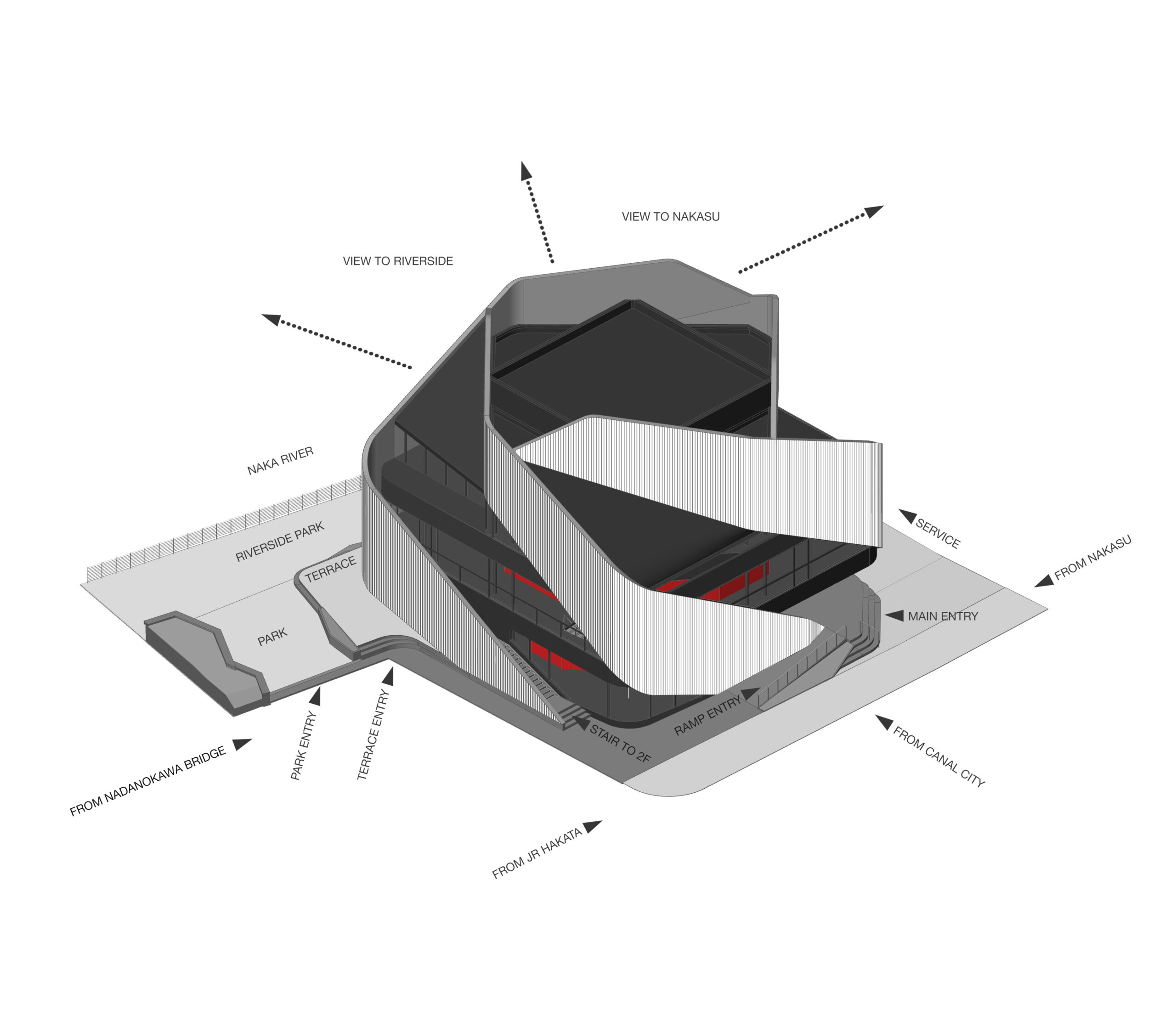

A finalist at the WAF Awards 2019 in the Future Projects Residential Category, MET Tirana is a 12-story residential and mixed-use building in the center of Tirana. At 160 feet (49 meters) tall, the project contributes to the city’s urban redevelopment plans, with a focus on maximizing pedestrian access at the ground level.

A finalist at the WAF Awards 2019 in the Future Projects Residential Category, MET Tirana is a 12-story residential and mixed-use building in the center of Tirana. At 160 feet (49 meters) tall, the project contributes to the city’s urban redevelopment plans, with a focus on maximizing pedestrian access at the ground level.