“A Field Guide to American Houses” at 40: Why This Classic Book Deserves a Place on Your Coffee Table

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

After pitching this article to Architizer’s managing editor, I spent a long time wondering how to approach it — what the “angle” should be.

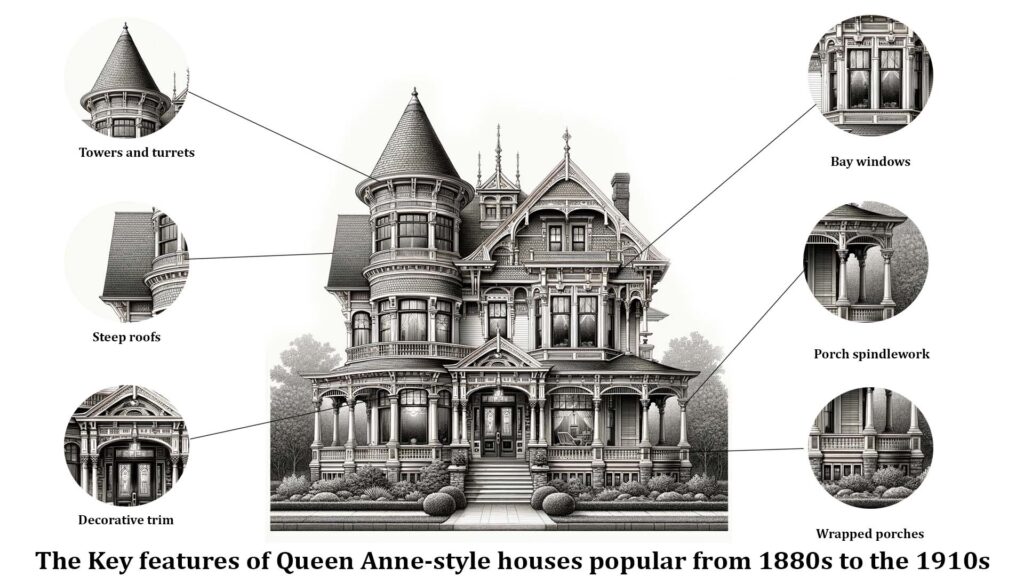

Finding reasons to praise A Field Guide to American Houses was of course not the problem. I have long known that Virginia Savage McElster’s book on vernacular American domestic architecture is as essential as air to anyone who loves historic homes. This is the book that taught me how to distinguish Georgian houses from Federal ones, and that Victorian is not a style of house but rather a period associated with a number of revival movements. (When people talk about “Victorian houses,” they are usually referring to the Queen Anne style). The pictorial glossary is still useful to me when I need to look up an architectural term (most recently, the difference between mullions and muntins), with a preference for a source that is more authoritative than what Google can cook up.

And yet, as easy as it would be to list the uses of the Field Guide, that isn’t quite enough to justify an article. It also doesn’t seem adequate to the book, whose most important virtue is not usefulness. The book is great because it is captivating.

The Shiels House was built in 1906 and is an unusual hybrid of Queen Anne Victorian and Prairie School with some Craftsman details. It is located in Dallas, Texas, the beloved home city of Virginia Savage McAlester. Renelibrary, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The secret of this book’s long standing success, I think, is that it inspires readers to take an interest in their own communities. Readers learn to appreciate that every block, every house, every window in their neighborhood has a story to tell. Even more than this, these elements are connected to a history, a language, that they can learn to decipher for themselves. The Field Guide teaches you how to read your neighborhood, and how to see that even new construction is tied to history, as all buildings exist in dialogue with what came before. Famously, its publication in 1984 led to the founding of preservation societies across the country, as readers gained a newfound appreciation for the built environment of their communities.

The layout of the Field Guide is very straightforward. This is unapologetically a reference guide that seeks to inform rather than editorialize. And yet, the lovingly assembled encyclopedic array of American domestic architectural types ranging from the Native American wigwam to the Split Level cannot help but inspire one to go out and start categorizing the houses in their neighborhood. I compare the experience of reading this book to learning about birdwatching. For birders who learn how to become sensitive to birdsong, the world outside becomes suffused with meaning. Suddenly, there is more in the environment that one can choose to attend to.

The greatest virtue of this book might be its accessibility. Each chapter begins with identifying details and photographic examples of the style in question. In the last section of each chapter, titled simply “Comments,” McElster provides some insight into where the featured style came from and how it fits into the history of architecture. While McElster’s tone is always neutral, one can pick up on a point of view. She has a special affection for the more ornate styles, especially Queen Anne houses. “Queen Anne Houses are among the most complex in architectural history,” she writes, “ornamenting every surface in sight. Even door hinges were embossed.” Indeed, there is nothing quite like a well preserved Queen Anne House, and McElster’s Field Guide did much to encourage interest in the preservation of these American masterpieces.

Ashishboora15, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Virginia Savage McElster passed away in 2020. The most recent update of the Field Guide was published in 2010 and included 600 new photos and line drawings of house types from 1940 to 2010. These chapters are just as captivating as those that preceded it, proving that architectural history keeps moving — but not in a linear direction. The most recent house styles she identifies, New Traditional and American Vernacular, are eclectic styles, defined by the way they recombine elements from the past.

There is a lesson in this, I think. By looking at architecture form a pedestrian, street-level points of view, emphasizing the types of homes people are likely to live in, McElster breaks away from some of the thematic narratives that dominate architectural discourse. The homes we live in aren’t demonstrations of ideas, they are environments cobbled together from multiple influences in order to serve a human function. Similarly, the Field Guide isn’t a treatise like so many other famous books on architecture — it’s a tour. There is no book that is more essential to an architect’s private library.

Cover Image: American Craftsman-style home at 1723 NE Naomi Place in the Ravenna-Cowen North Historic District, Seattle, Washington. Guywelch2000, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

The post “A Field Guide to American Houses” at 40: Why This Classic Book Deserves a Place on Your Coffee Table appeared first on Journal.