The Rigor of Making: Inside the Barcelona Studio of Flores & Prats Architects

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

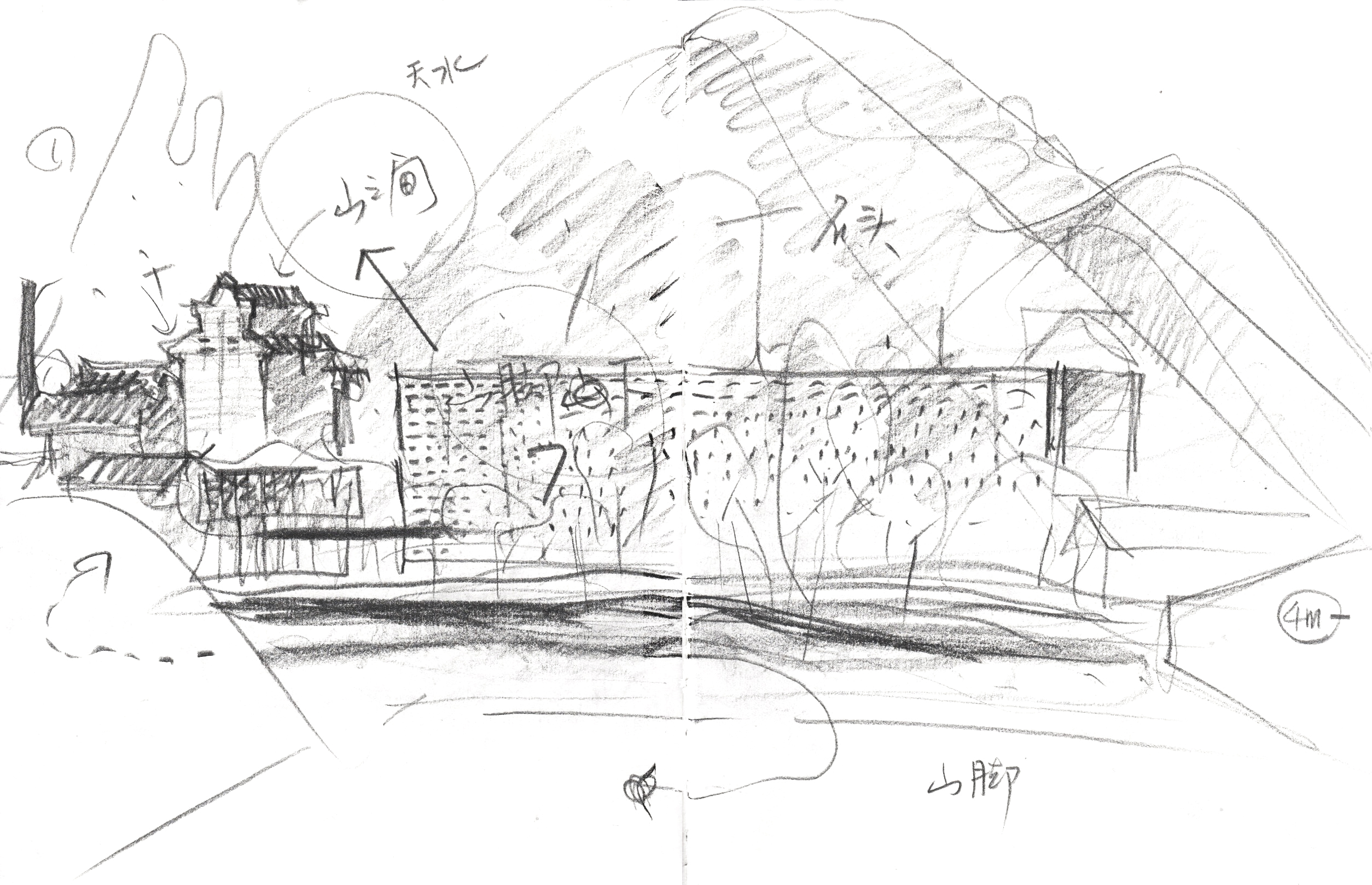

Imagine a table covered in large sheets of tracing and drafting paper. Pencils, markers and a set of rulers, of all shapes and sizes, are scattered along its surface. Vast amounts of masking tape hold in place overlapping drawings and images. An architect’s desk lamp illuminates the work surface, shedding light to the rubber crumbs, pencil shavings and smudges — unavoidable traces of hand drawing that reveal a different type of (architectural) practice, a practice of “making.”

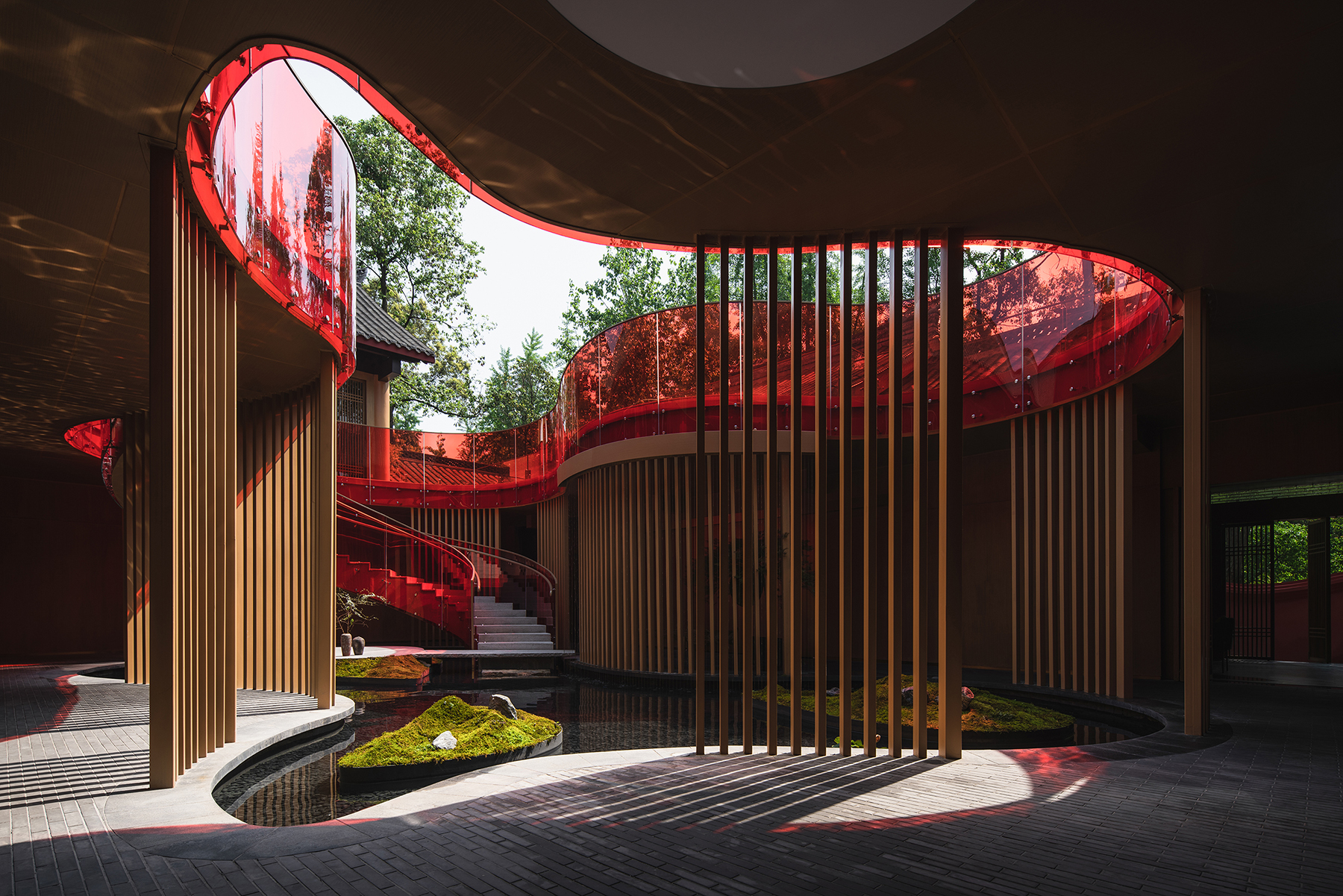

Located in Barcelona’s historic center, the Flores & Prats Architects is not exactly a typical architectural workspace. It lacks the “cleanness” often found in contemporary firms, where open-plan spaces are inhabited with large tables, used for arranging iMacs in an orderly manner in addition to housing the occasional desk plant. Instead, this particular studio is split into a series of (domestic) rooms, where models are stuck on the walls and ceilings, drawings spill out of cupboards, and tables on wheels are always in a state of wonderfully curated mess.

Flores & Prats was founded in 1998 by Eva Prats and Ricardo Flores and combines design and constructive practice with academic activity. The studio looks at research as a driving tool for architecture, producing countless projects open to public interpretation and critical thinking. The practice is internationally recognized; it has been awarded countless prizes throughout the years and its work has been exhibited in monographic and collective exhibitions, while their first monograph book Thought by Hand. The Architecture of Flores & Prats offers insights into their unique method of working.

Describing the Flores & Prats studio feels quite romantic in today’s context. It is reminiscent of an era where the architect was viewed less like a producer and more as a sceptic, with hand drawing being a tool for inquiry as well as communication. As a result, when considering the lack of technology in the studio’s process, my question is: How do they do it? How are they able to not only survive in such a fast paced world but actually thrive in it without taking advantage of technology’s “benefits”?

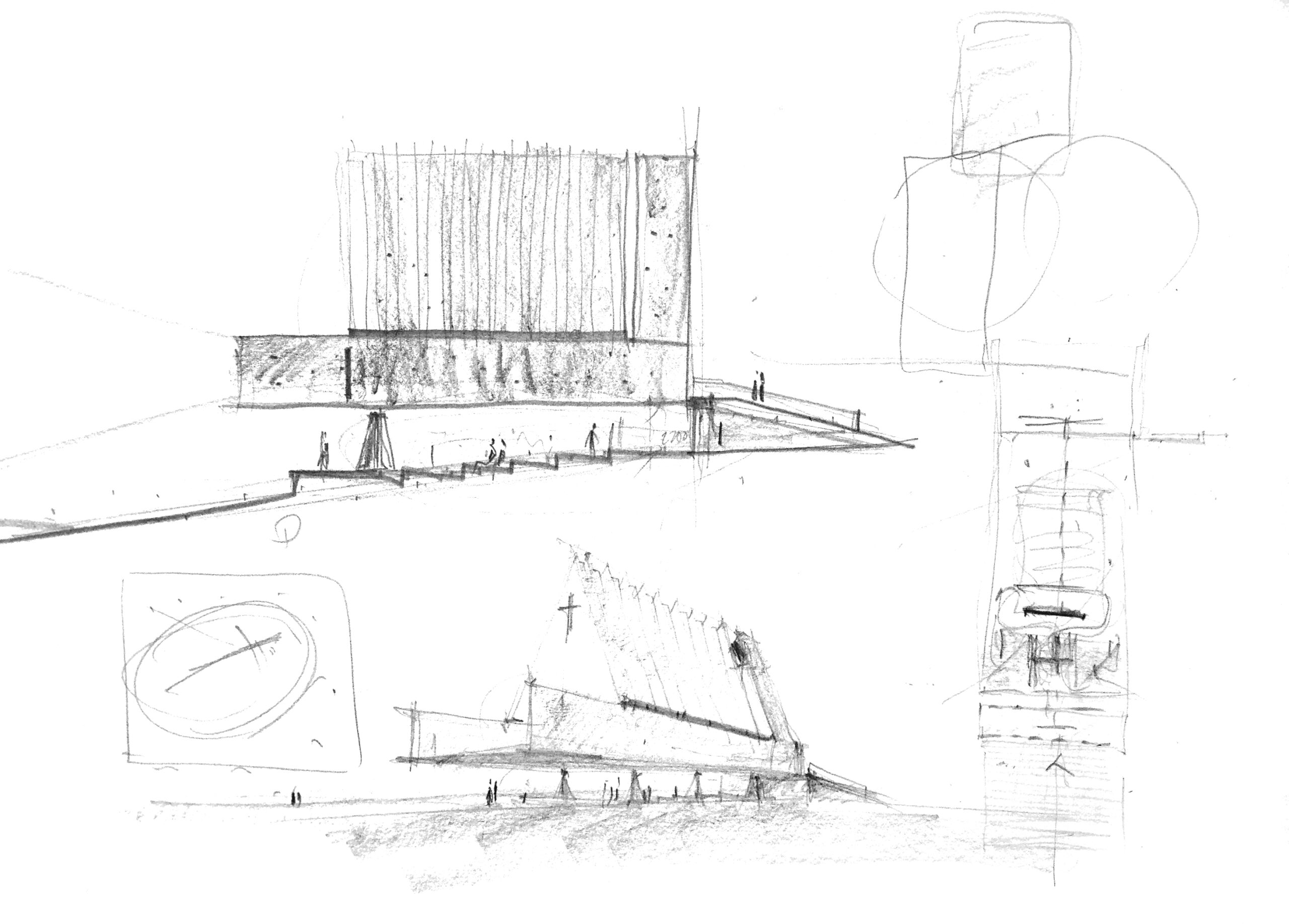

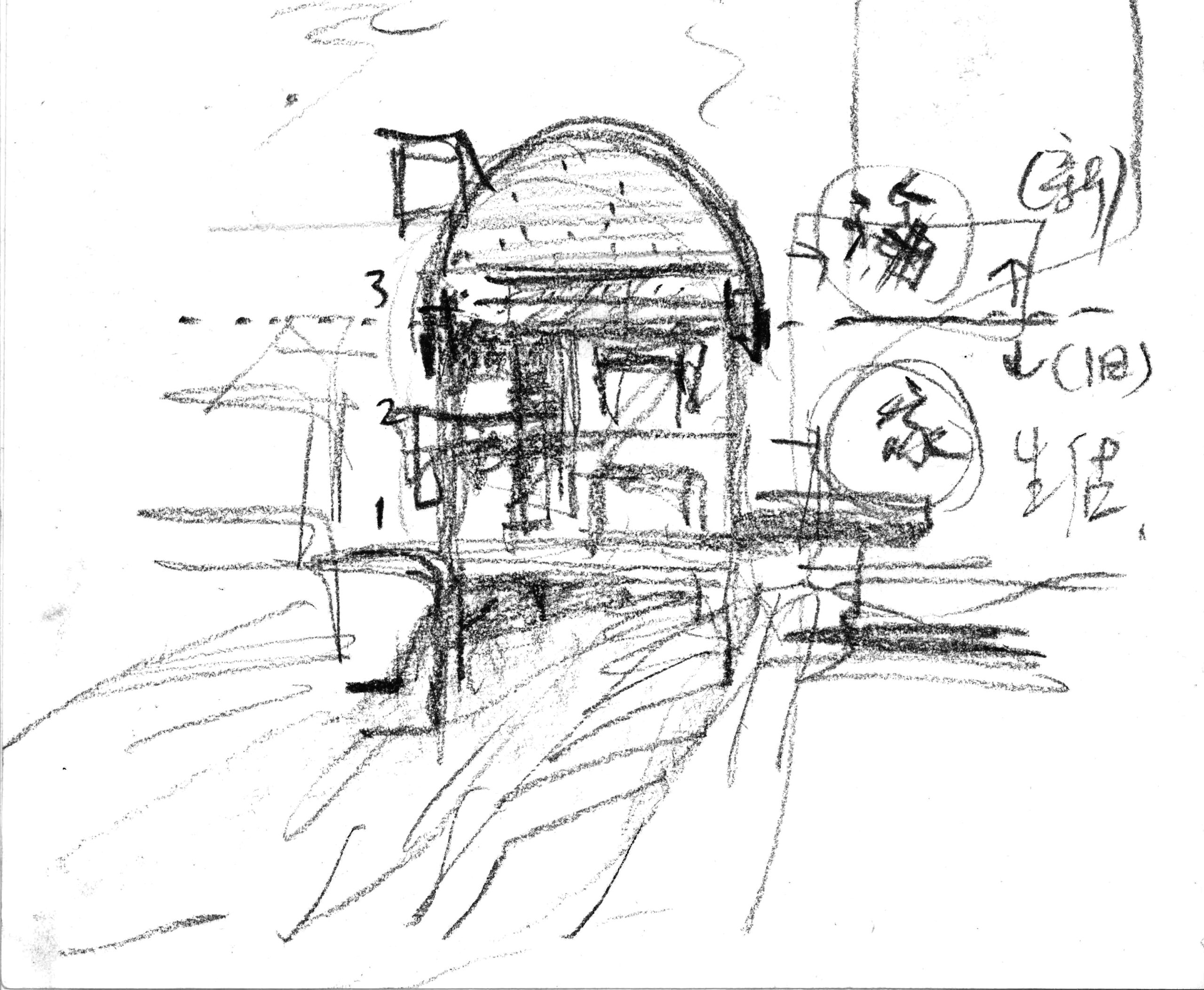

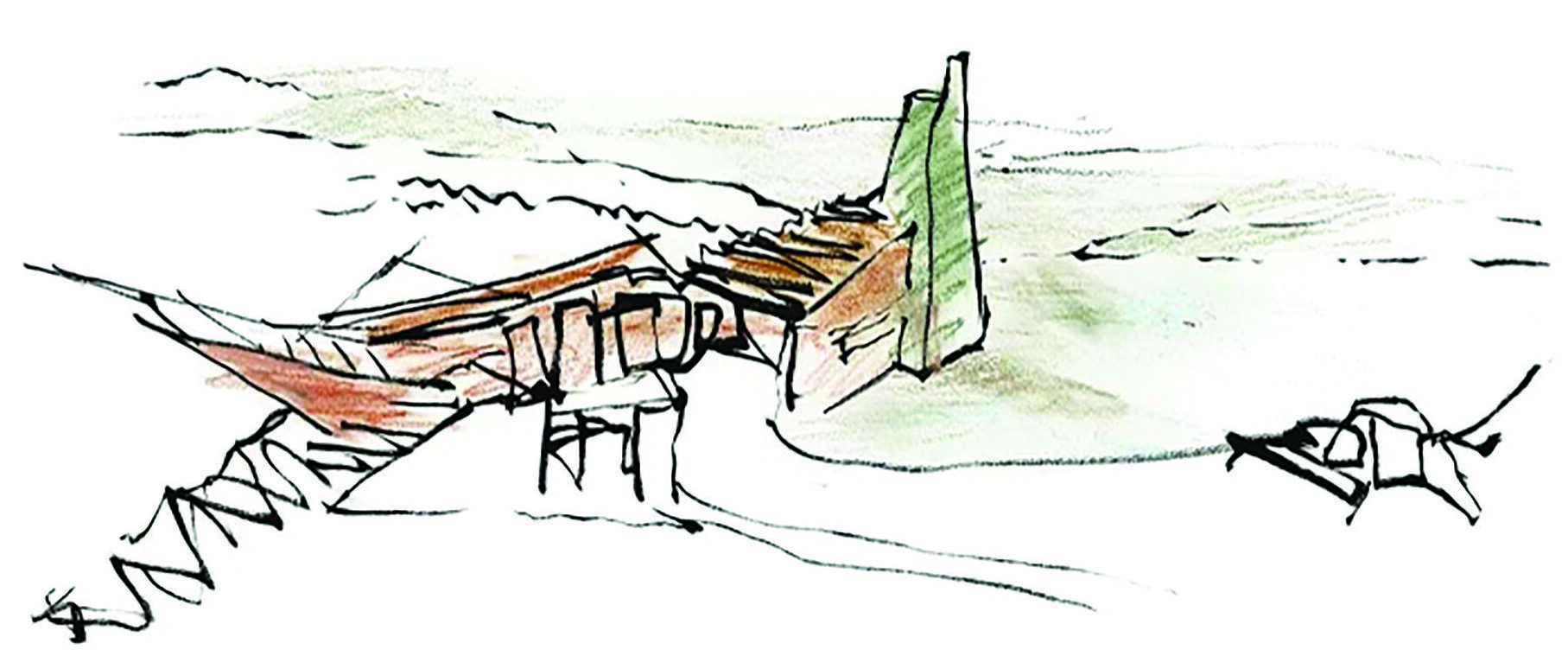

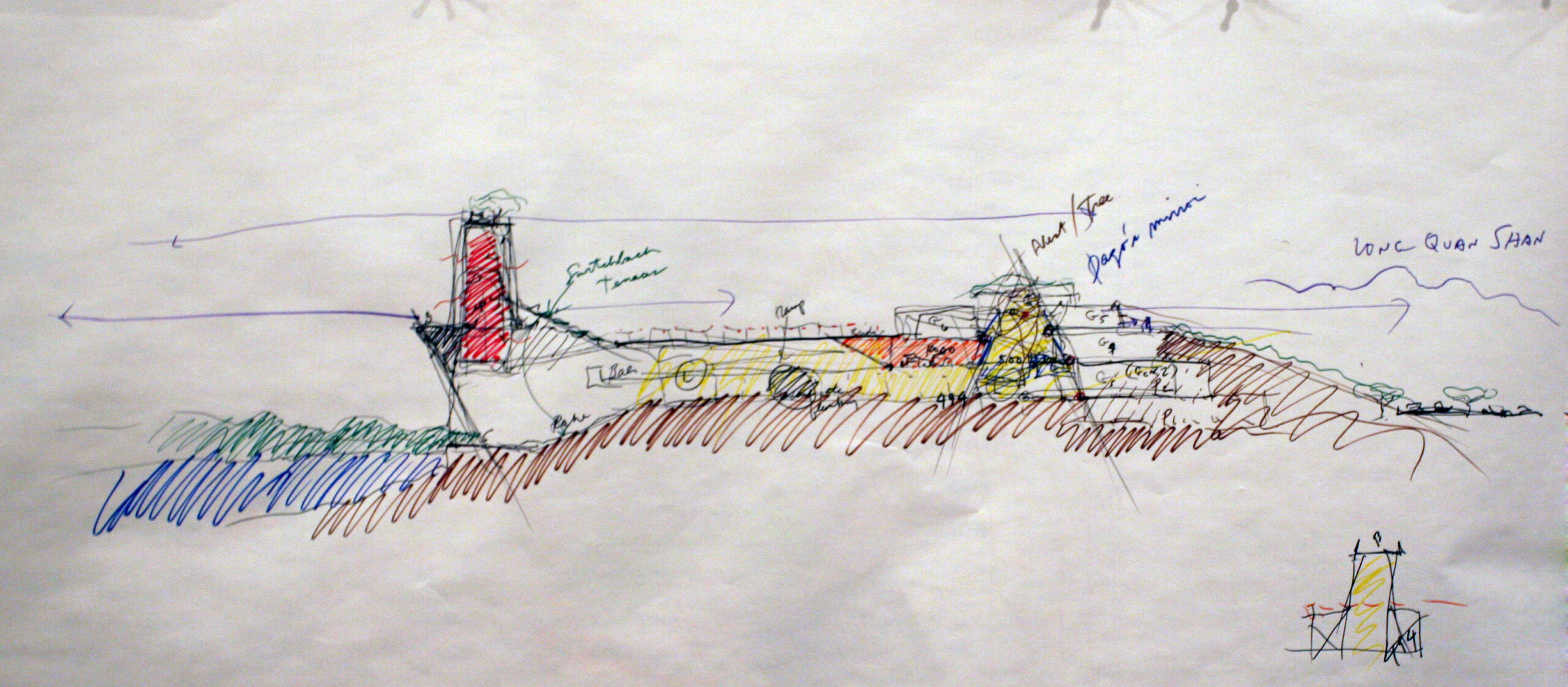

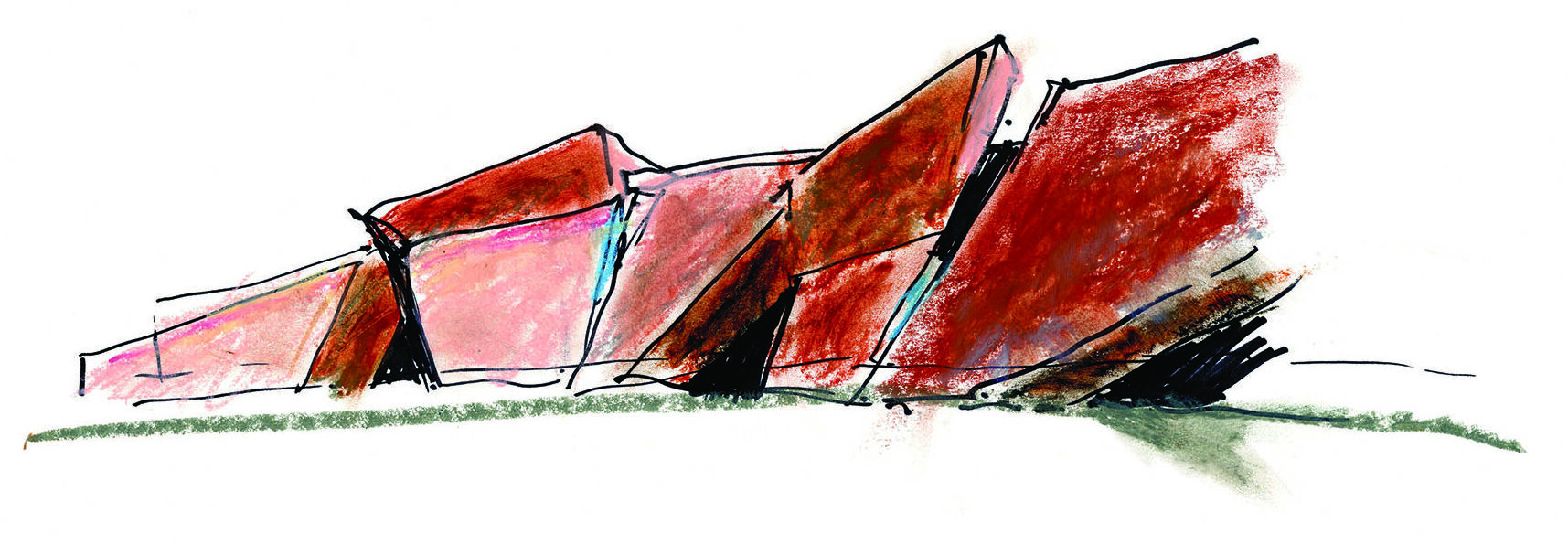

Eva Prats and Ricardo Flores are huge advocates of hand drawing and by extent model making. According to them, analogue practices are inherently slow, allowing room for imagination and uncertainty, crucial ingredients for making responsive architecture. By abandoning the immediate precision required when using today’s software, the hand is free to explore and flow through a range of ideas, rather than focus on resolving a single one. It becomes a way of thinking.

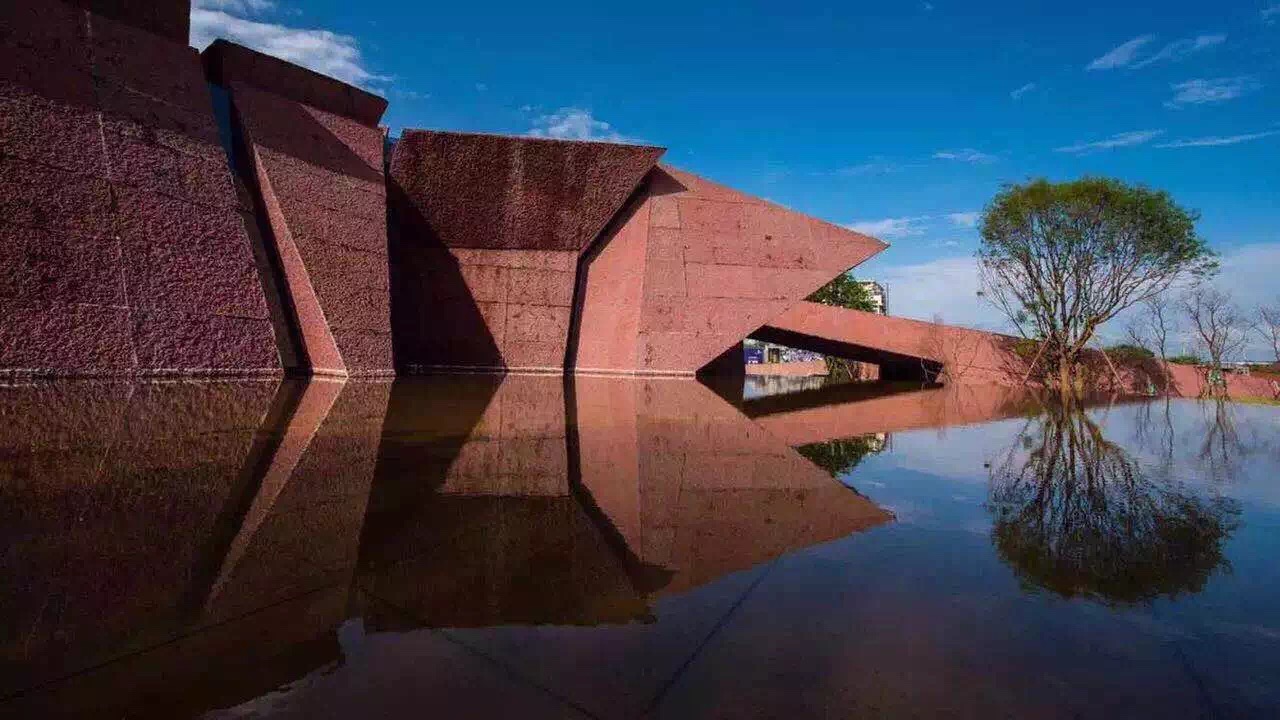

Still, the studio’s drawings are quite unique, deviating from the rules of technical drawing, and merging scales, mediums, views and most importantly intent in a single page. Heavily influenced by their time with Enric Miralles, both Eva Prats and Ricardo Flores incorporate multiple aspects of a project in a single drawing. Through a single blueprint (as they call it) they are able to observe and record a space through time, superimposing different surveys, which — especially in their older projects such as Sala Beckett and the Casal Balaguer — directly inform the design. Additionally, in their later work, collaborative projects such as Edificio 111, required a different type of superimposition, where the blueprint acted as a container and testing of ideas, incorporating diverse opinions and expertise, fitting every contribution onto the page.

Flores & Prats’ recent exhibition as part of La Biennale di Venezia 2023, titled Emotional Heritage and curated by Lesley Lokko, opens up discussions around unfinished drawings, models and films. The exhibition material was arranged on four tables: ‘The open condition of the ruin;’ ‘The right to inherit;’ ‘Drawing with time;’ and ‘The value of use,’ which look into memories, civil and moral values and stories that reside within abandoned buildings and reveal the invisible social relationships that operate within them. Once again, hand drawing is crucial in this process, recording the buildings’ temporal dimensions, the spatiality of ruins, the accumulation of cultural elements (doorframes, windows, tiles, scrapes of plaster) and, finally, the pressures of ownership.

I am aware that I have barely scratched the surface on the studio’s methods and processes. However, one thing is abundantly clear: it all starts with a table. For Flores & Prats, the table becomes a surface for interaction, collaboration and inquiry, where drawings that describe so much more than the form and the construction of a building can occur. A place, where time slows down and projects develop beyond the given timelines and demands of the assignment. Even though it is not easy to ignore the pressures and demands of the contemporary architectural field, the Flores & Prats studio has proven the benefits of testing out more and producing less for the built environment, taking the time to truly explore the makings of inhabited space.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Featured Image: ARCH.architecture, FLORESPRATS-SALABECKETT-62408-PH 04 Old and new window connecting the Bar with the Vestibule photoAdriàGoula, CC BY-SA 4.0

The post The Rigor of Making: Inside the Barcelona Studio of Flores & Prats Architects appeared first on Journal.