The Why Factory (T?F) by MVRDV: The Potential of a Visionary Architectural Think-Tank

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

The Why Factory (T?F) is a global think-tank founded in 2008 and led by Winy Maas, founding partner of MVRDV and Professor of Urbanism and Architecture at the Delft University of Technology. It explores possibilities for the future development of cities by utilizing innovative methods of production and visualization. It analyses, theorizes and constructs scientific and fictional city scenarios in order to tackle contemporary urgencies — both global and local, universal and specific. Since its inception, The Why Factory has organized an array of exhibitions, publications, workshops and panel discussions, in an attempt to foster public debates on architecture and urbanism.

That is the traditional (rigid) way of introducing such research groups; by stating their timeline, their goals, their process and their output. However, what is unique regarding The Why Factory is the primary question it asks: Why be visionary? and I would also add, why is it important to be a visionary architect in today’s world? In the Why Factory’s first publication, Visionary Cities in 2009, Winy Maas extensively discusses the need for and potential of visionary thinking in architecture and urbanism:

“A vision is, in a way, what happens between a question mark and a proposal. It asks the big questions and then paints an image for the future with its answer. Most importantly, it is a dream for the city and for its spatial translation that offers a long-term, cohesive, seductive, and strong perspective for future societies. It is part curiosity, part exploration, part fantasy, and part real problem solving. The role of the visionary is to guide, and direct and summarize the course for this increasingly urban world.”

The world, according to Mass, is currently caught between globalization and individualism. With the rise of technology and the internet, any human can now work, communicate and socialize through their own individual screen; their location does not matter anymore. Even the most secluded farm in the Highlands can have the same virtual access to someone living in a large metropolis. In parallel, country borders have faded. The world can be seen as one large city, dealing with crises (financial, environmental, etc.) which are no longer localized, but rendered as global challenges.

For Mass, the answer to those two ‘extremities’ — as he calls it — is vision. Frankly, the use of this word causes great scepticism and fear amongst people, often related to either too narrow-minded, too politically motivated and too bureaucratic or on the other hand, too extreme. Nevertheless, visions can uncover wider collective desires, still stemming from individuals but eventually pointing to wider goals that, in the case of architecture, create new spatial environments that look forward and stage a more optimistic future.

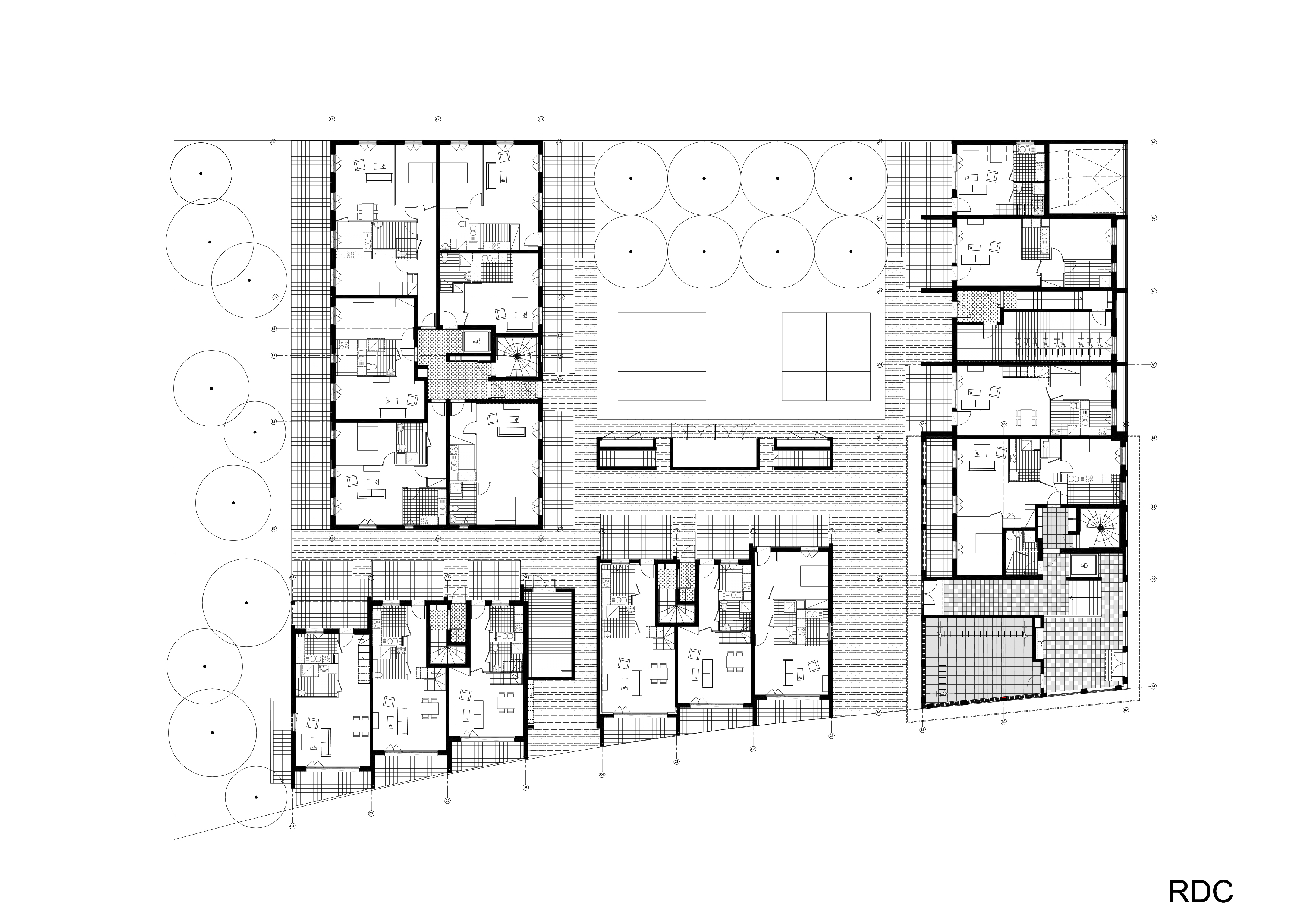

Wego: Tailor-made Housing

The project starts with the hypothesis that by establishing a participatory process in housing design, where each resident can create their house based on their unique desires, then cities would achieve maximum density by optimizing land use, combating inequality as well as limiting the threat of urban sprawl.

The research was a joint effort between The Why Factory, the students from TU Delft and IIT Chicago, RMIT Melbourne and Bezalel Academy Jerusalem. Initially, students were presented with a challenge to convert density into desire, while following a restricted urban envelope with low energy consumption. Eventually, they developed a game that acts as a typological puzzle and pairs different clients, cultures and desires, resulting in a unique housing intensity.

The Green Dip

The project investigates architectural strategies that incorporate plants into buildings by going back to the basic questions: ‘why green? What are its capacities? How does green perform? How can green be implemented to our cities? Can we create a database of plant species? Can we create a software to help us, do it? Can we invent a series of green elements to be implemented?’

Instead of designing a building, a park or anything else that speaks green, the researchers created a new software tool that combines the knowledge of buildings with the knowledge of plants, titled The Green Maker. The software includes a database of 4500 plants, outlining their water needs, total weight, maximum height, oxygen production and CO2 absorption, a catalogue of parametric elements that enables the placement of grasses, shrubs, and trees on any surface in and around buildings as well as additional biome data that ensures that only native plants are selected for each specific site.

AnarCity: When Do We Need Our Neighbors?

The project investigates and designs the anarchistic city, i.e., a city without rules. It asks, ‘aren’t city’s overruled?’ claiming that in most major city’s nowadays, especially the highly dense ones, rules and top-down governance bodies restrict freedom, particularly when it comes to urban uniformity. By using an interactive generative process, tested on an abstract city model as well as in real cities, the project explores the relationship between density and anarchy, arguing that even though rules do provide solutions to societal conflicts, a truly advanced society would be the one where anarchy is not associated with chaos and danger but rather as a collective agreement to certain rules, enforced equally by city inhabitants.

As a final note, I would like to point out that The Why Factory is an exemplary synergy between architectural practice and architectural education. Driven from both academic and professional perspectives, this research group tackles “architectural vision” in a way that bridges the gap between speculative thought and practical application, making The Why Factory not only a pioneer in architectural research but also a critical incubator for the next generation of visionary thinkers and practitioners.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Featured Image: Why Factory Tribune by MVRDV, 132, Julianalaan, Delft, Netherlands

The post The Why Factory (T?F) by MVRDV: The Potential of a Visionary Architectural Think-Tank appeared first on Journal.

Minimalism, once synonymous with stark, all-white spaces, is evolving into something more human and inviting. Enter Like maybe”warm minimalism,” a design philosophy that retains the clarity of minimalism but infuses it with warmth through organic textures, earthy tones and subtle contrasts. This evolution isn’t about abandoning minimalism altogether, it’s about making it human.

Minimalism, once synonymous with stark, all-white spaces, is evolving into something more human and inviting. Enter Like maybe”warm minimalism,” a design philosophy that retains the clarity of minimalism but infuses it with warmth through organic textures, earthy tones and subtle contrasts. This evolution isn’t about abandoning minimalism altogether, it’s about making it human.

In another corner of the design world, a subtler movement is taking shape. It’s not flashy, and it doesn’t shout for attention.

In another corner of the design world, a subtler movement is taking shape. It’s not flashy, and it doesn’t shout for attention.

The connection to nature will be stronger than ever in 2025. Perhaps it’s a reaction to the increasing digitalization of our lives or maybe it’s simply a return to something fundamental: the feeling of being grounded. Biophilic design is about more than just plants. It’s about designing homes that breathe, that feel alive in the way they interact with their surroundings. Picture sunlight pouring through oversized windows, warming floors made of natural bamboo.

The connection to nature will be stronger than ever in 2025. Perhaps it’s a reaction to the increasing digitalization of our lives or maybe it’s simply a return to something fundamental: the feeling of being grounded. Biophilic design is about more than just plants. It’s about designing homes that breathe, that feel alive in the way they interact with their surroundings. Picture sunlight pouring through oversized windows, warming floors made of natural bamboo.

And then there’s silver. For years, brass and gold have dominated our homes, offering a sense of glamour. But silver is different. It’s quieter, subtler—less about the spotlight and more about the glow. Silver accents are finding their way into kitchens, bathrooms, and living spaces. Imagine a matte silver faucet in a kitchen where earthy brick tones dominate, or silver-framed mirrors reflecting the warmth of a softly lit bedroom. It’s an element that bridges the old and the new, a versatile accent that feels fresh without overshadowing the rest of the room.

And then there’s silver. For years, brass and gold have dominated our homes, offering a sense of glamour. But silver is different. It’s quieter, subtler—less about the spotlight and more about the glow. Silver accents are finding their way into kitchens, bathrooms, and living spaces. Imagine a matte silver faucet in a kitchen where earthy brick tones dominate, or silver-framed mirrors reflecting the warmth of a softly lit bedroom. It’s an element that bridges the old and the new, a versatile accent that feels fresh without overshadowing the rest of the room.

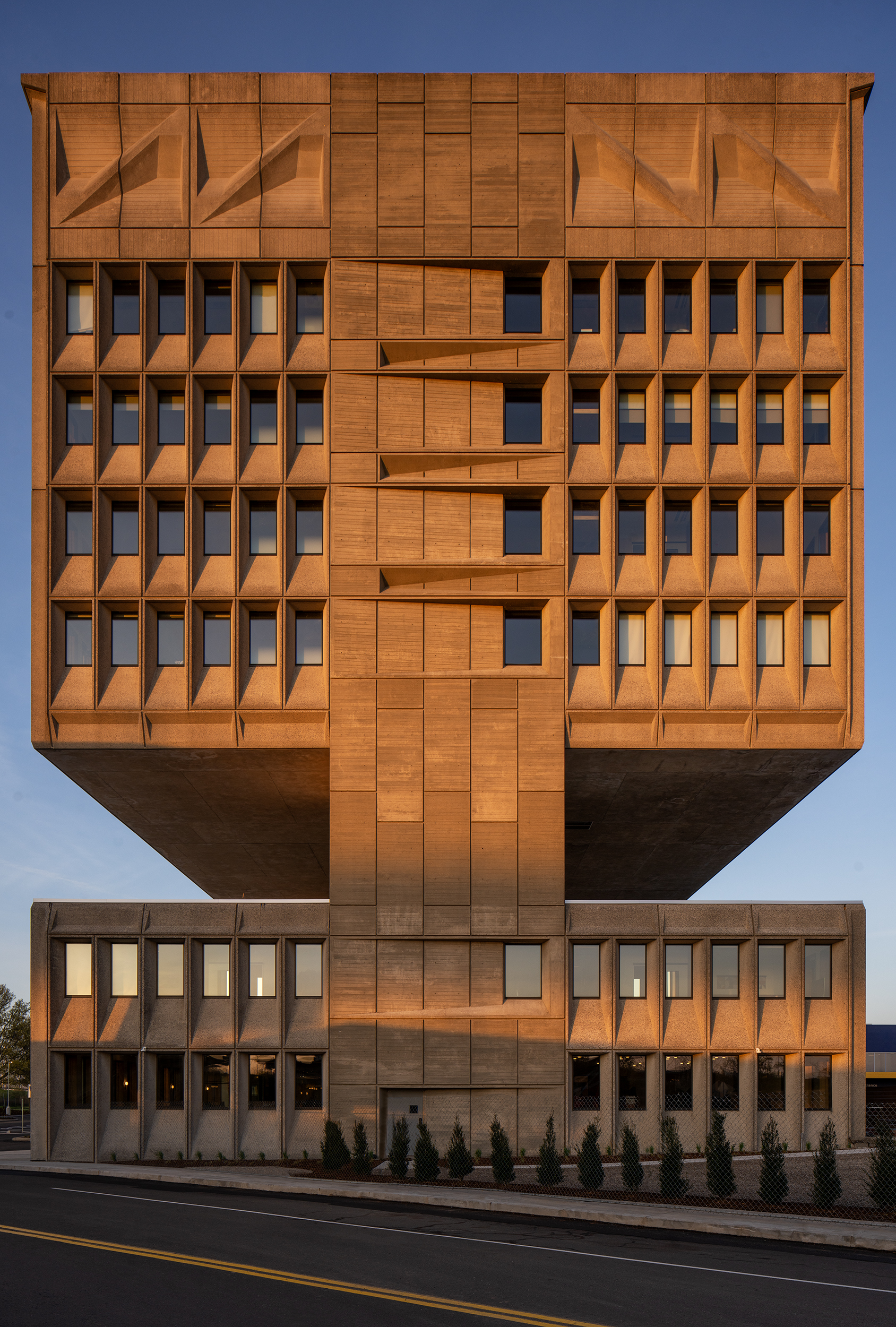

1. Earthy Tones

1. Earthy Tones

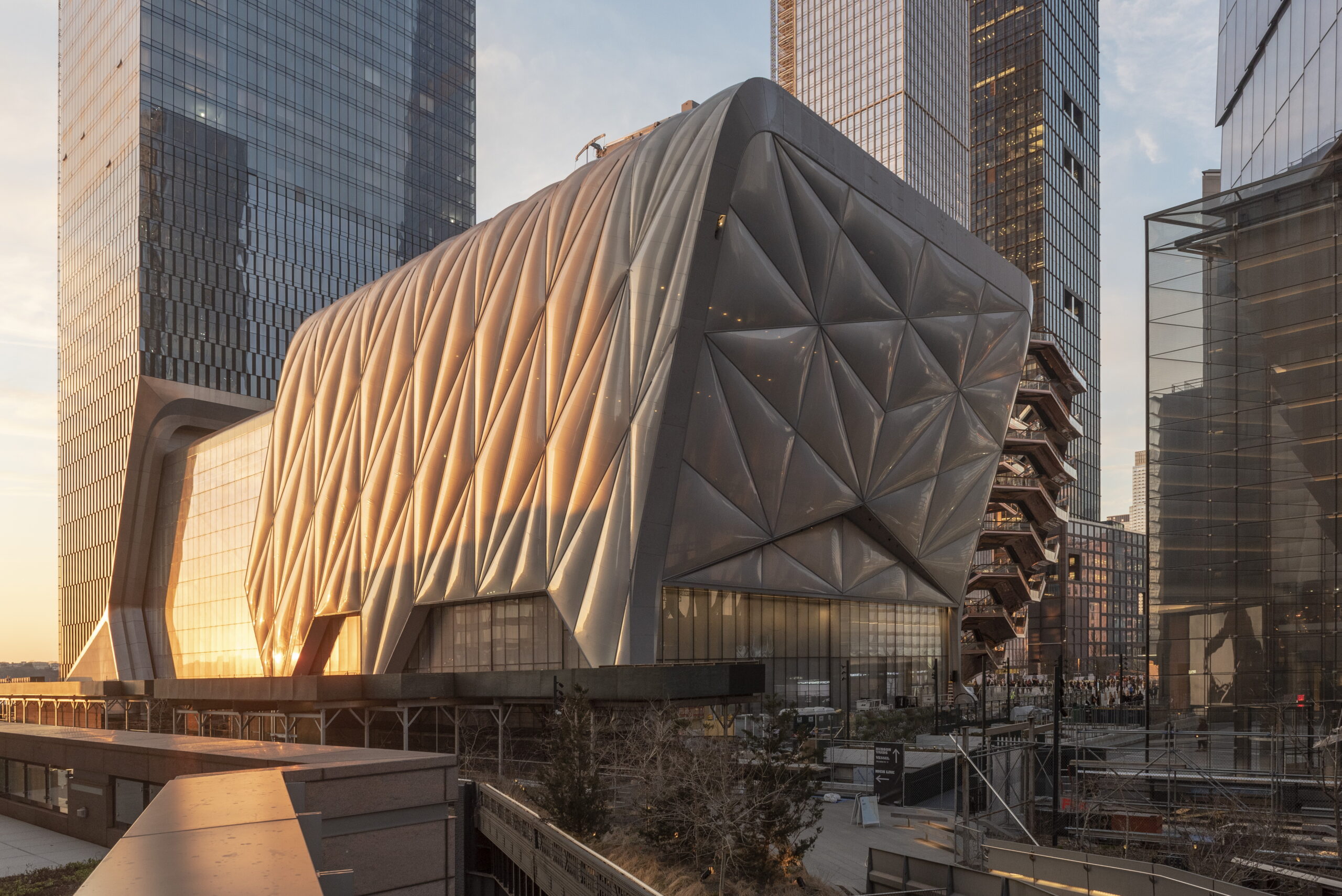

Texture is a powerful design tool that goes beyond visual aesthetics, offering tactile and structural qualities that enrich the experience of a building. For 2025, mixing materials on exteriors (and interiors) has become a defining trend, creating a layered, multidimensional look that’s as functional as it is beautiful.

Texture is a powerful design tool that goes beyond visual aesthetics, offering tactile and structural qualities that enrich the experience of a building. For 2025, mixing materials on exteriors (and interiors) has become a defining trend, creating a layered, multidimensional look that’s as functional as it is beautiful.

At the heart of these trends is a deepening commitment to sustainability. Homeowners are no longer just asking, “What looks good?” They’re asking, “What lasts?” Brick, with its natural origins and timeless appeal, is a perfect example. Made from clay or shale, it’s durable, energy-efficient, and recyclable. Other materials, like bamboo and reclaimed wood, offer similar benefits, combining beauty with eco-consciousness. The result is homes that feel good to live in — and good to live with.

At the heart of these trends is a deepening commitment to sustainability. Homeowners are no longer just asking, “What looks good?” They’re asking, “What lasts?” Brick, with its natural origins and timeless appeal, is a perfect example. Made from clay or shale, it’s durable, energy-efficient, and recyclable. Other materials, like bamboo and reclaimed wood, offer similar benefits, combining beauty with eco-consciousness. The result is homes that feel good to live in — and good to live with.