From Load-Bearer to Space-Maker: Considering the Contemporary Column

Ema is a trained architect, writer and photographer who works as a Junior Architect at REX in NYC. Inspired by her global experiences, she shares captivating insights into the world’s most extraordinary cities and buildings and provides travel tips on her blog, The Travel Album.

Columns, one of the most fundamental structural elements in architecture, have long transcended their functional purpose to become powerful aesthetic and spatial tools. In contemporary architecture, particularly within open-plan designs, the use of columns is not limited to supporting the weight of a structure. Instead, architects have used columns to frame spaces, guide movement, create a sense of rhythm and bridge the gap between structure and art.

Through the manipulation of their size, placement and materiality, columns are employed to define spatial experiences while preserving the openness and fluidity inherent in open-plan designs. In this article I explore how different architects utilize columns to create open-plan elegance while highlighting the architectural depth and intention behind some of their designs.

The Evolution of Columns in Architecture

Columns have been a fundamental part of architectural history, with origins dating back to ancient civilizations like Egypt, Greece and Rome. Initially, columns served purely as load-bearing elements, essential for supporting the massive stone roofs of temples, palaces and public buildings. The early use of columns, particularly in classical architecture, was driven by necessity, with their design focused on stability and proportion. From the slender, fluted Doric columns of Greek temples to the ornate Corinthian pillars that adorned Roman basilicas, columns were both functional and symbolic, representing power, order and permanence.

Today, the role of columns has evolved dramatically. In modern architecture, particularly within open-plan and minimalist designs, columns are no longer confined to their structural function. Instead, they have transformed into tools of spatial expression, playing an active role in shaping environments, guiding movement, and even blurring the boundaries between art and architecture. Their presence creates rhythm and flow within a space, while their materiality, form and placement contribute to the spatial identity of a design. In this way, columns continue to be transformative, moving from simple supports to sophisticated elements that enhance the architectural experience.

SANAA’s Nuanced Treatment of Columns

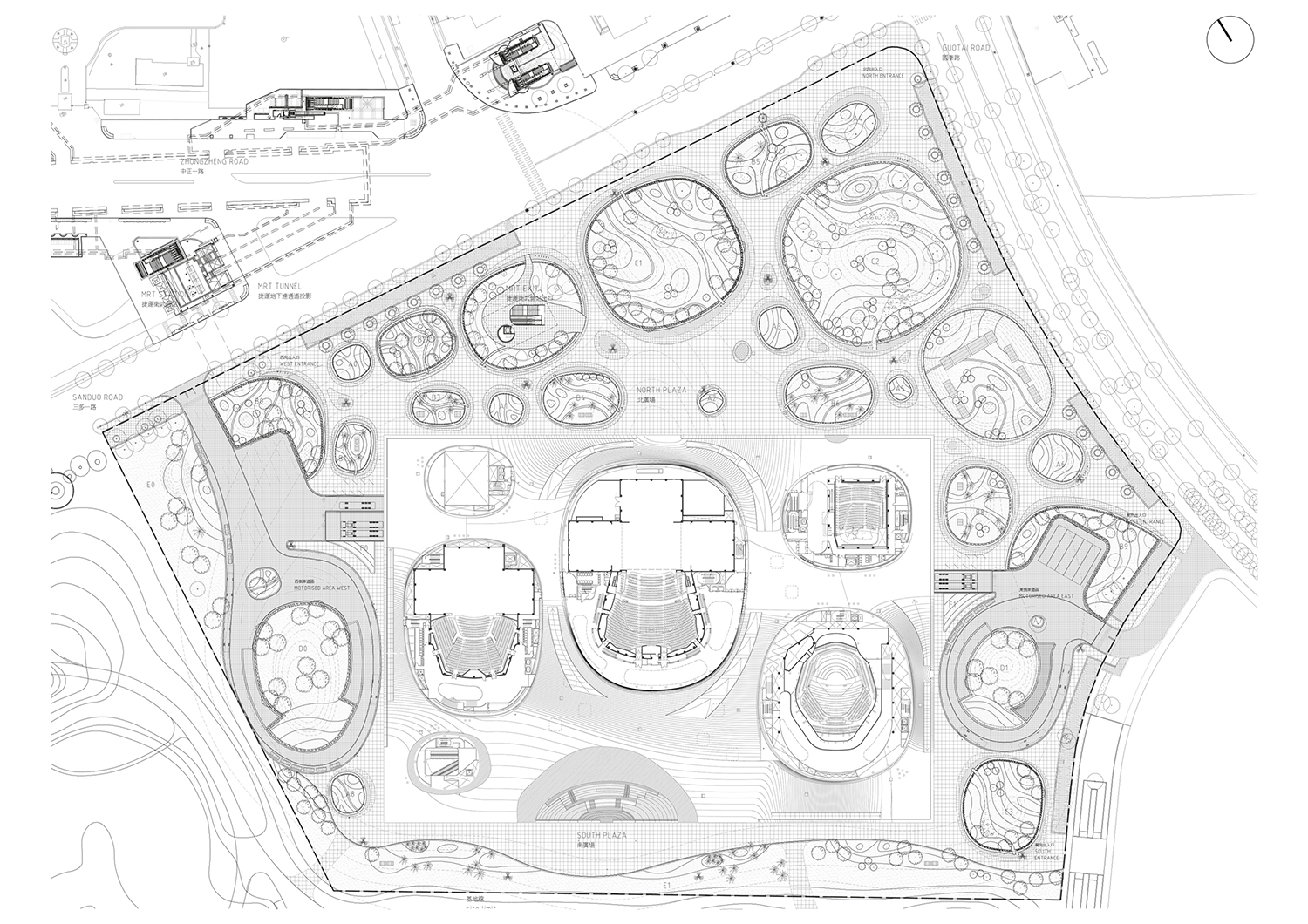

Grace Farms by SANAA, New Canaan, Connecticut

It’s safe to say that anyone in the world of architecture is familiar with SANAA, the renowned Japanese architectural firm led by Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa. Their work is a prime example of how the role of columns in architecture can be reimagined, transforming them into far more than structural supports. In their work, columns take on a poetic dimension, becoming subtle yet powerful tools that shape the spatial experience. By embracing transparency and minimalism, SANAA integrates columns in ways that seem to dissolve the boundary between interior and exterior, creating spaces that feel fluid, open, and light. Their approach to columns often emphasizes delicacy and elegance, with slender, almost invisible supports that allow the architecture to feel as if it is floating, rather than being firmly anchored to the ground.

This nuanced treatment of columns fundamentally alters the way people interact with their buildings. Rather than perceiving columns as obstacles or purely functional elements, occupants engage with them as part of the architectural language. The columns frame views, define pathways and contribute to the ethereal quality of their building’s designs. In projects like the Louvre-Lens Museum, the Glass Pavilion at the Toledo Museum of Art or even Grace Farms, the columns are strategically placed to guide movement through the space, creating an experience that is both dynamic and serene. This delicate balance between transparency and support challenges conventional perceptions of structure, making the columns integral to how people perceive and use SANAA’s buildings — both as a part of the architectural narrative and as an active influence on how the space feels and functions.

The Psychology of Columns

Harvard Art Museums by Renzo Piano Building Workshop, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Columns play a subtle yet powerful role in shaping the psychology of how people perceive and experience a space. Their design, placement and materiality can influence emotional responses and perceptions in significant ways. Repeated columns create a sense of rhythm and order, fostering stability and calm, while also framing views and guiding the eye toward specific focal points, enhancing engagement with the environment. The scale of a column also affects how people perceive a space — grand, imposing columns evoke awe and a sense of grandeur, whereas slender columns make a space feel light and approachable.

Additionally, columns guide movement through a building, subtly directing how people navigate, explore or pause within the space. Their arrangement also impacts the sense of openness or enclosure; closely spaced columns can create intimacy and privacy, while widely spaced columns maintain openness while structuring the flow. The materiality of columns — whether stone, glass or metal — further affects the psychological experience, influencing perceptions of strength, transparency or modernity. Altogether, columns shape both how we interact with a space and our emotional connection to it, making them essential to the psychology of architectural design.

Jun’ya Ishigami’s Organic Chaos

Kanagawa Institute of Technology KAIT Workshop by Junya Ishigami+Associates, Kanagawa, Japan

Where SANAA employs columns to reinforce minimalism and transparency, Jun’ya Ishigami takes an entirely different approach in his design for the Kanagawa Institute of Technology (KAIT) Workshop. Here, columns become the primary spatial organizers, transforming the open-plan layout into an environment that feels organic, almost chaotic, yet deeply intentional. Ishigami’s use of columns in this project represents a radical departure from the conventional grid-based column arrangement; instead, the columns are placed randomly, with varying heights and thicknesses, creating a forest-like atmosphere.

The irregular placement of columns in the KAIT Workshop serves a dual purpose: it challenges the traditional notions of order and structure in architecture while simultaneously offering flexibility and adaptability in the use of space. The columns, rather than being simple supports, are designed to evoke natural elements, like trees in a forest, blurring the boundaries between the built environment and nature. This randomness creates a non-hierarchical space where no single area is privileged over another, allowing for fluid interaction between the users and the architecture.

Ishigami’s intention with this design is to foster creativity and interaction within an open, undefined space. The columns do not dictate specific functions for different areas; instead, they encourage users to interpret the space in their own way. In this sense, the columns become more than structural supports; they act as spatial generators, shaping the way people move through and inhabit the space. In contrast, Jun’ya Ishigami’s approach to columns is more experimental, often challenging conventional perceptions of structure and space. His columns tend to be whimsical, irregular, and sometimes even exaggerated in their presence. Rather than disappearing into the background, Ishigami’s columns assert themselves, creating surreal, dreamlike environments.

Unlike SANAA’s fluid transparency, Ishigami’s columns actively shape and distort space, often creating a sense of wonder and unpredictability. Both architects push the boundaries of column use, but in distinctly different ways — SANAA toward invisibility and elegance, Ishigami toward experimental and immersive spatial play.

Renzo Piano: Functional Rhythm in Museum Design

Kimbell Art Museum Expansion by Renzo Piano Building Workshop, Fort Worth, Texas

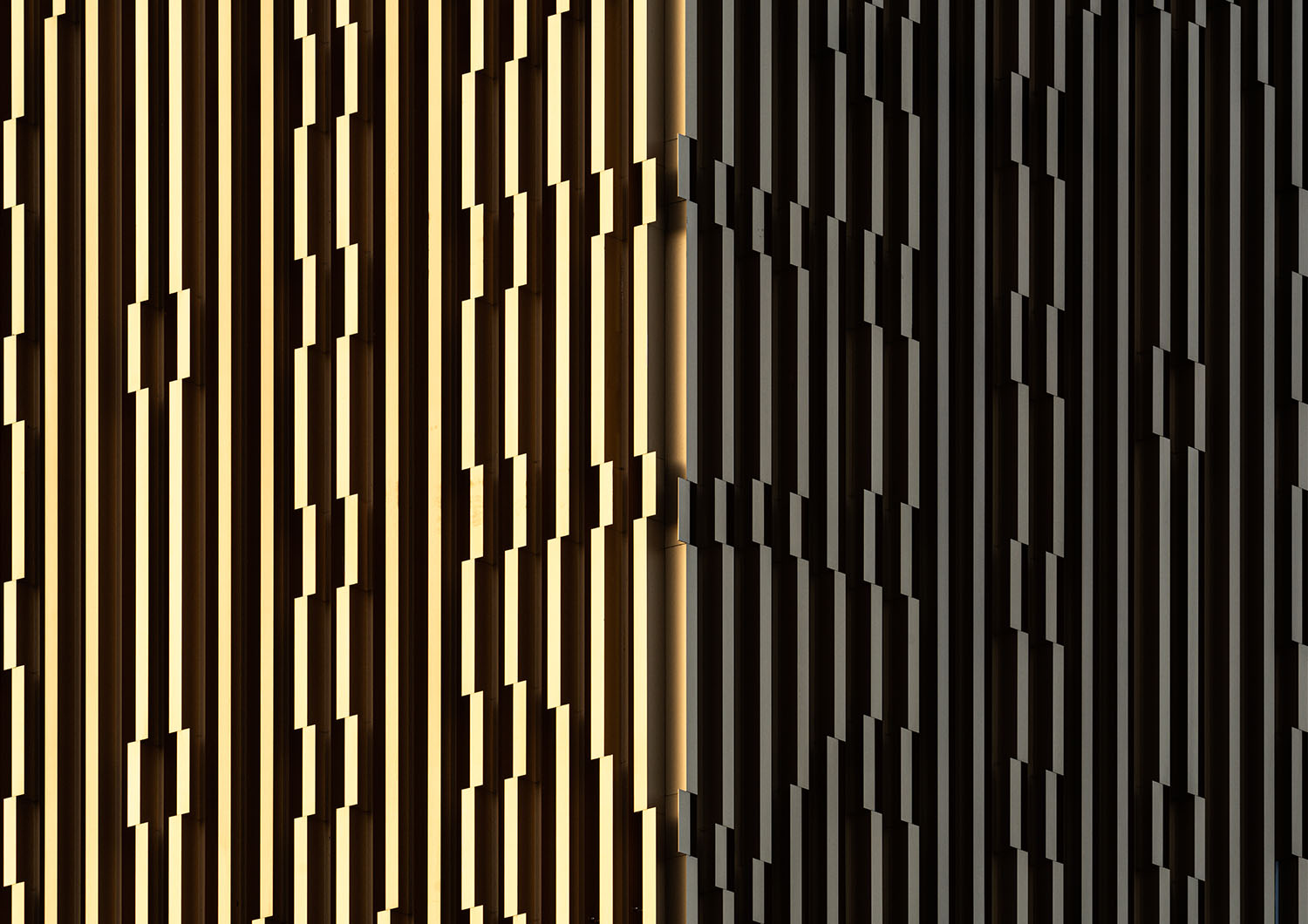

Another architect who masterfully employs columns to shape space is Renzo Piano, particularly in his extension of the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. In this project, Piano integrates a series of steel columns into the design, creating a subtle but powerful rhythm that defines the spatial experience. He uses columns in a refined and deliberate way to shape the space, alter the experience, and influence the interaction between people and architecture. Unlike others who use columns as bold visual statements, Piano’s use of columns is understated, allowing the architecture to remain the backdrop to the art it houses.

The steel columns in the Kimbell Art Museum extension are placed along the glass façade, framing views of the landscape while maintaining the openness of the gallery spaces. The columns are slim and carefully positioned to ensure that they do not interrupt the flow of space, while still providing the necessary structural support for the expansive glass walls. Here, Piano’s use of columns is about creating a balance between transparency and enclosure, allowing natural light to flood the interior while maintaining a sense of openness and connectivity with the surrounding environment. The columns act as framing devices, both literally and metaphorically, guiding the viewer’s gaze and shaping the way the space is experienced.

The columns play an integral role in the blurring of boundaries between structure and space. They influence how visitors perceive the architecture—not just as a series of rooms, but as a cohesive experience where the structure itself becomes part of the artistic narrative. This rhythm shapes the visitor’s experience, influencing the pace at which they move through the space and the way they engage with both the art and the architecture.

Columns are far more than mere structural supports; they are pivotal elements that shape the way we perceive, experience and interact with architecture. The way architects think about and utilize columns can dramatically transform spatial design, influencing everything from the flow of movement to the emotional and psychological impact of a space. Whether they create rhythm, frame views, guide circulation or define openness, columns play a crucial role in the relationship between structure and experience.

As architecture evolves, the role of columns continues to expand, allowing them to transcend their functional origins and become tools for artistic expression, spatial transformation, and human engagement. How we think about and use columns is essential not only to the integrity of buildings but also to the richness of the environments we inhabit. They shape our experience of space in ways that are both subtle and profound, making them one of the most fundamental elements in the language of architecture.

The 13th A+Awards invites firms to submit a range of timely new categories, emphasizing architecture that balances local innovation with global vision. Your visionary projects deserve the spotlight, so start your submission today!

The post From Load-Bearer to Space-Maker: Considering the Contemporary Column appeared first on Journal.