What if the World Built All the Paper Architecture Proposals?

The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.

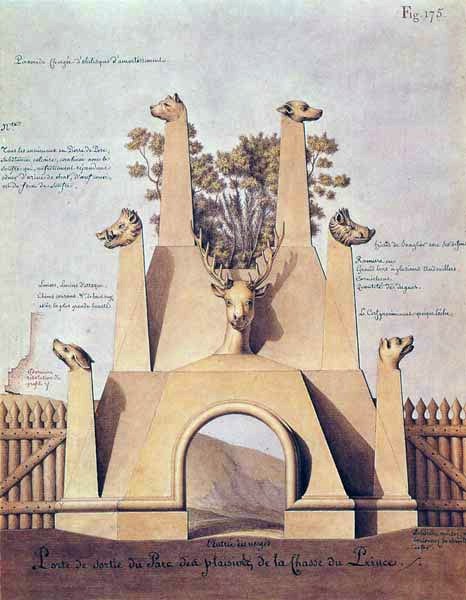

Floating structures, plug-in cities, human pods, flying machines and buildings with walking tentacles. These are only a few of the speculative designs architects throughout the years have developed in an attempt to push the boundaries of the discipline forward and respond to the many challenges the global built environment is facing. From early drawings such as Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Imaginary Prisons and Jean-Jacque Lecque’s Gate of a Hunting-Ground, speculative or “paper” architecture has been a subject of great experimental “release” since the 18th century.

Even though they stay only on paper, these designs hold such enticing qualities not only due to the impeccable drawings that represent them but also for the fictional stories they tell. Through them, design and construction methods are questioned, and real-world problems are solved, thus becoming a source of inspiration for architects throughout the world. Especially during the 1960s-1970s, avant-garde architects spawned some of the most influential architectural movements of that time.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu creator QS:P170,Q1684923, Lequeu Tor eines Jagdgelaendes Projekt, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons

Archigram

Possibly the most well-known group of speculative architects, Archigram’s unbuilt projects were developed after WWII, in an attempt to reevaluate the way in which people lived in urban centers. Plug-in City and Walking City were some of their most provocative projects, utilizing hypothetical technology to create energy efficient structures that introduced concepts such as movable cities, modular architecture and even nomadic living.

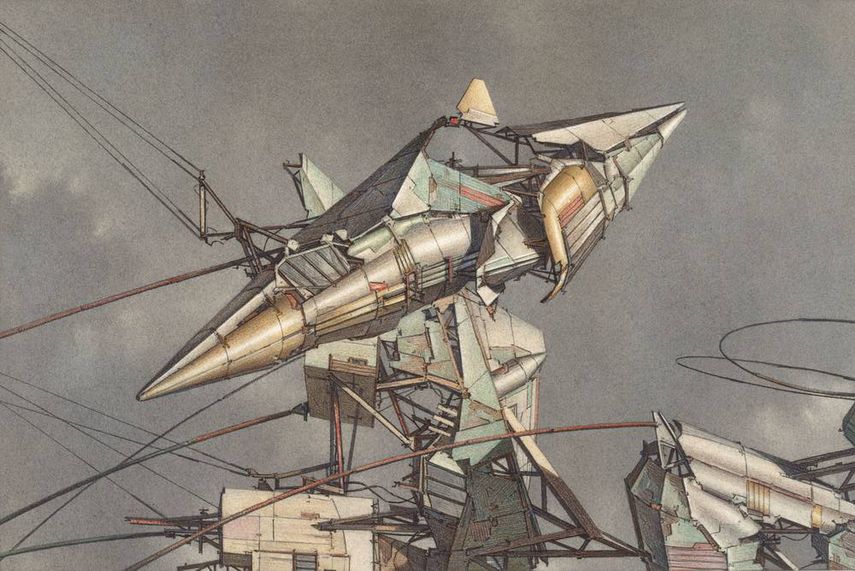

Lebbeus Woods

Geomagnetic Flying Machines. © Estate of Lebbeus Woods

During his career Lebbeus Woods focused on architectural theory and experimentation and co-founded the Research Institute for Experimental Architecture. Although his designs were unshackled by the constraints of the real world, i.e. finance, build-ability and technology, his work deals greatly with existing issues such as rebuilding post-war cities and architecture as a defense mechanism towards political upheavals. The Sarajevo Window for example, is a proposal for a wall and window repair after the Bosnian capital underwent terrorist attacks in the 1990s.

Gaetano Pesce

The Italian architect and designer and his project the Church of Solitude addressed immigration issues and a corporate way of living. When experiencing New York in the 1970s, he witnessed large groups of people living together in ‘helter-skelter’ conditions and thus developed the concept of an underground church fit for introspection, contemplation and a retreat from the city’s institutional culture. Pesce’s excavated landscape became a refuge underneath the imposing, capitalist Manhattan skyscrapers.

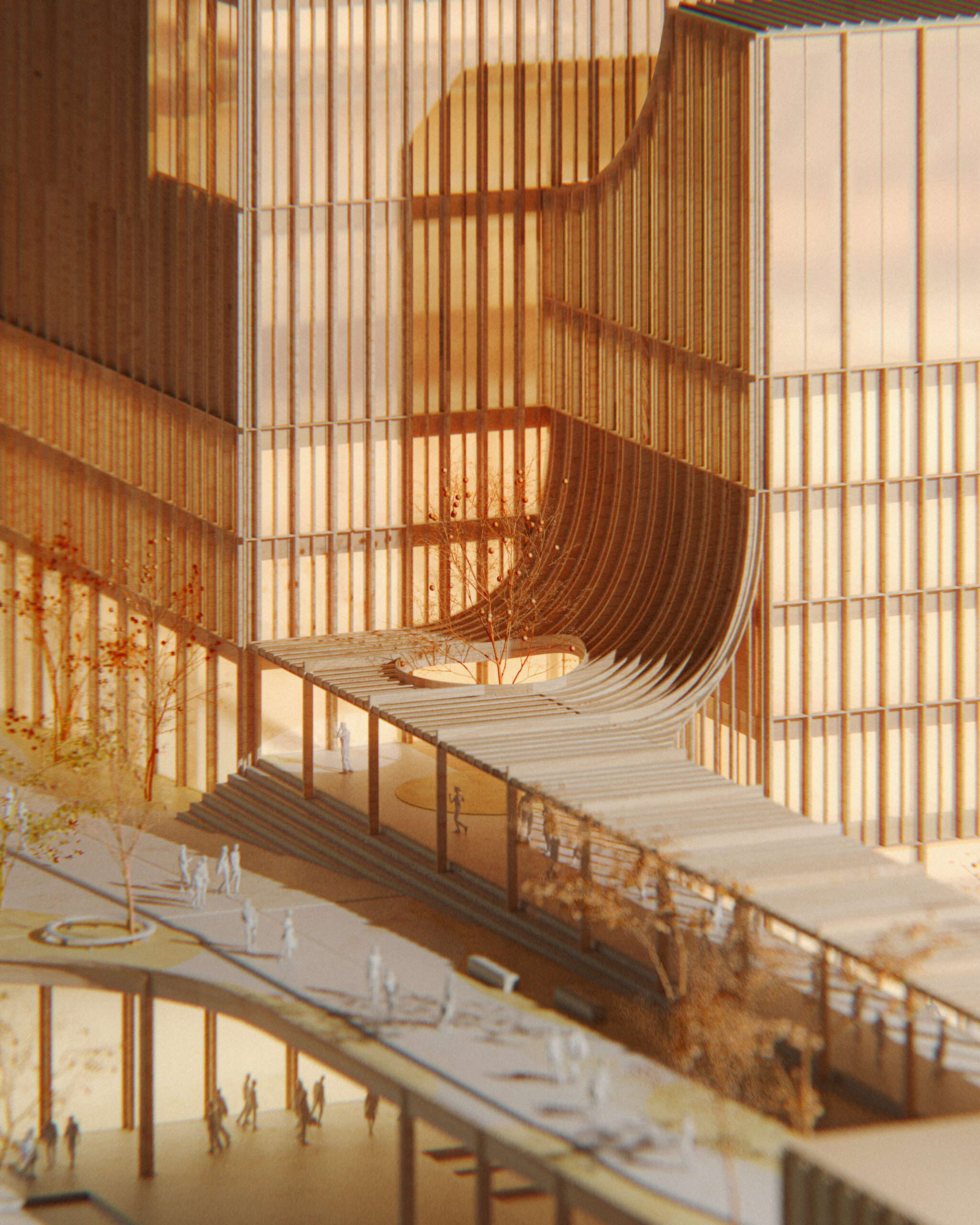

We are now a couple of decades later and still; paper architecture hasn’t lost its allure for architects. There have been countless speculative proposals, breathtaking drawings and models as well as an abundance of theoretical and contextual writings that reveal that intent behind these designs.

CJ Lim

Food City is CJ Lim’s most recent project, in which he positions food in the core of national and local governance and influence the way in which a city is both spatially and functionally organized. The architect creates a hypothetical case study showcasing how a secondary environmental/food infrastructure can operate as a sustainable stratum over the city of London.

Bryan Cantley

“Machno-morphic” is one of the characterizations that vividly describes Bryan Cantley’s work, which is comprised of speculative drawings that reflect upon the remains of mechanical realities within the landscapes of Southern California. He delves into the region’s folklore, which mixes dreams of a suburban peace with Spanish Colonialism and mountainous landscapes, proposing future mechanical forms (instruments) that investigate, critique and oftentimes compliment the western industrial setting.

Perry Kulper

Perry Kulper’s proposals reach ‘implausible dimensions’. His drawing practices explore new ways of immersive design, investigating how architecture interacts with its cultural environment. Beyond inventing new modes of architectural representation, Kulper’ work looks at real places, landscapes and contexts and composes an array of possible and unexpected interactions between them.

After exploring examples of paper architecture drawn in the past 50 years, it is safe to say that all these projects, albeit speculative, contain more than a dash of realism in them. They are practical interventions, situated in cities that face real-world challenges and propose solutions that tackle climate change, social housing, immigration, experiential design, food production, industrial production and so much more.

At this point I want to borrow Lebbeus Wood’s quote stating that ‘architecture is always constrained by the reality of technology.’ In other words, building all these paper architecture proposals is not impossible; it is merely a matter of whether technology can keep up with human imagination. The optimist in me believes that if we were to implement these designs with the same liberal manner in which they were conceived, i.e. breaking free from ulterior political and economic motives, architecture would truly and holistically impact our cities, our natural landscape, our resources and even reevaluate the (currently concrete) norms through which humans inhabit the planet.

The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.

Featured image: Giovanni Battista Piranesi artist QS:P170,Q316307, Piranesi01, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons

The post What if the World Built All the Paper Architecture Proposals? appeared first on Journal.

Kalina Prelikj: You’re a trained architect and have been working in the industry for some time. What led you to shift your focus from designing buildings to capturing them through photography and visualization?

Kalina Prelikj: You’re a trained architect and have been working in the industry for some time. What led you to shift your focus from designing buildings to capturing them through photography and visualization?