The Complicated Case of Polykatoikia, Athens’ Famous Postwar Apartment Blocks

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Homogenous. Boring. Bulky. Ugly.

These are some of the characterizations Athenians use to describe the buildings in which they live. The famous polykatoikia is a multi-housing apartment block whose name derives from poly, meaning many, and katoikia, meaning residence. This dominant morphological form has shaped Athens’ architectural identity since the early 20th century.

In 1933, a group of architects, theoreticians and artists boarded the ship Patris II to travel from Marseille to Athens to carry out the CIAM IV Conference (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne) titled “the Functional City”. Le Corbusier (architect), Fernand Léger (artist), Christian Zervos (art critic) and Siegfried Giedion (architectural historian) irreversibly shaped the future of Athens’s built environment by advocating and promoting the modernist movement, thus inspiring Greek architects to produce the first designs of the Athenian Polykatoikia.

Until the 1950s, polykatoikias slowly overshadowed the many two-story neoclassical houses that stood as the predominant form of residence throughout the city. However, in the late 1950s, following the devastating losses of the Second World War and the Greek Civil War, large parts of the population were leaving the countryside to migrate to the country’s capital in search of a better life. Consequently, the need for housing in Athens grew exponentially, and a new law, antiparochi, was created that changed the trajectory of the city’s urban layout forever. The law of antiparochi allowed landowners to exchange their plots for ownership of some of the apartments in the new polykatoikia constructed on their land, resulting in the erection of countless polykatoikia buildings in record time.

The positive effects of antiparochi were that the people from the countryside managed to find not only homes but also jobs in the construction industry. However, throughout the polykatoikia bloom, which mostly took place during the 1950s through to the 1980s, most of the buildings were not designed and materialized by architects but rather by contractors, who would relentlessly copy the basic morphological features, leading to the production of many uninspiring, identical multi-housing units. As a result only a few architectural “gems” can be found in a sea of repetitive concrete blocks. Furthermore, due to the rapid construction, any attempt for proper urban planning practices could simply not keep up and, as a result, polykatoikias were above the control of building regulations and often situated in areas without any proper infrastructure.

If a person asks a present-day Athenian whether they find their city beautiful, the most likely response would be “No.” The aspiration of an Athens filled with neoclassical buildings, which was initially brought to the city by western European philhellenes, is a recurring 21st century dream. Nevertheless, this was not the case for the 1950s “modern” housewife. The polykatoikia introduced a functional way of living, filled with new amenities that were unprecedented at that time. People who lived in neoclassical houses had no immediate access to water, no preinstalled heating system and often had to go outside to use the bathroom facilities. The carefully decorated and carved façades, although beautiful and somewhat reminiscent of the (glorious) ancient Greek past, did not satisfy the needs of the 20th century Athenian.

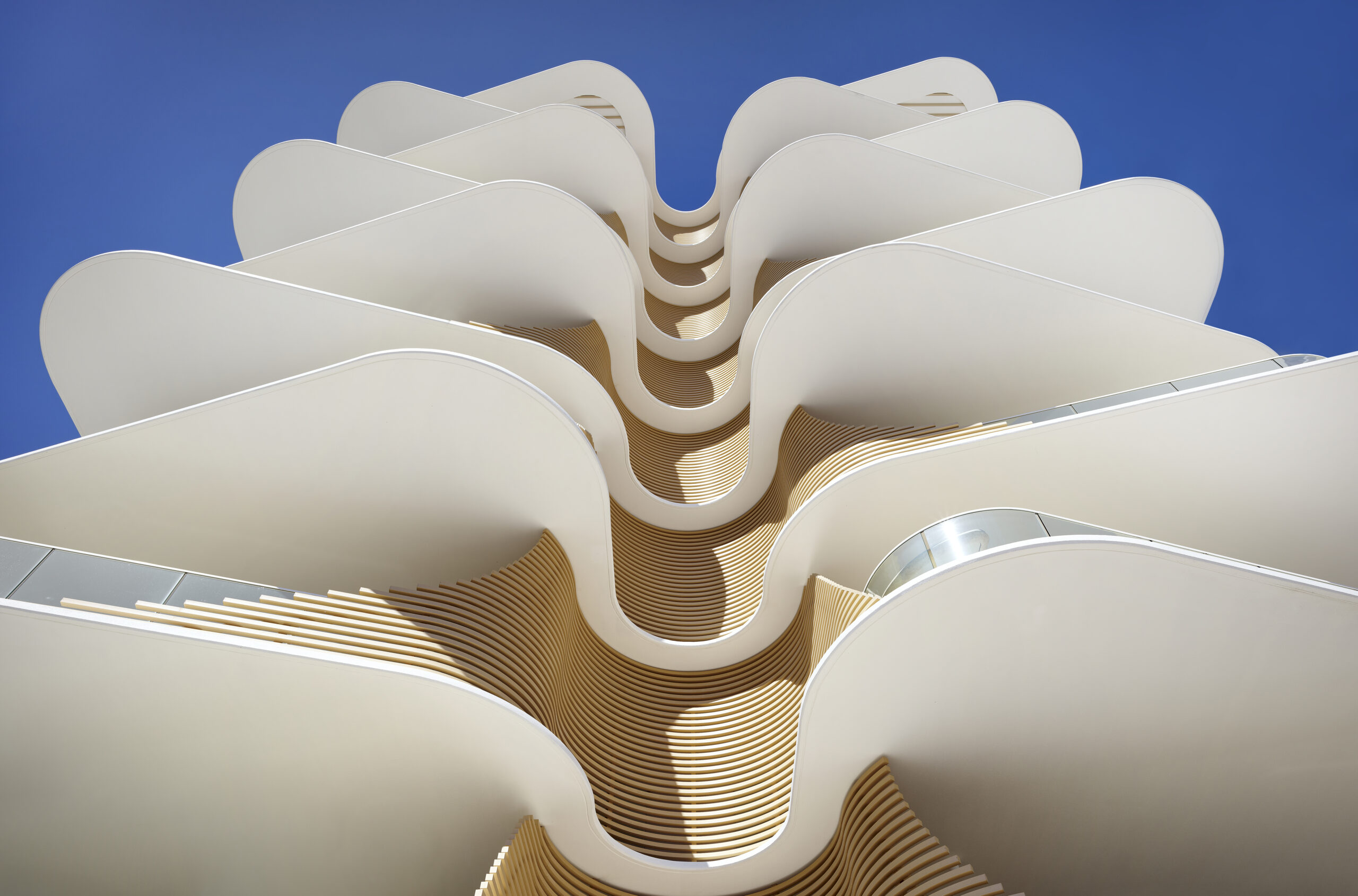

Torre della Nostlagia by 314 architecture studio, Athens, Greece

Furthermore, the polykatoikia introduced a new social organization. For the first time in history, wealthy and poor were living in the same building and neighborhood. In a typical polykatoikia, the ground floor would most likely be a shop, a café, a restaurant or a bar, then the first couple of floors would be occupied by the lower social classes while the upper floors would house wealthier families; in fact, in later years some apartments would be turned into workspaces and, more recently, Airbnbs. This groundbreaking and totally spontaneous functional and social organization resulted in a city that seams homogenous but is actually the complete opposite: it is a vibrant built environment that truly never sleeps.

Residential building by Kordas Architects, Athens, Greece

Still, almost 50 years have passed since the glorious days of the polykatoikia and it is time to reflect once more. Athens is currently facing an array of predominantly environmental problems, where a concrete “carpet” has covered entirely the natural landscape of the Attica basin. Amidst the concrete there are almost no green spaces, the existing rivers flow underground and Athens has become the hottest city in Europe. Fortunately, the “mix” of social classes has been preserved however, the growing tourist waves and golden visa initiatives are threatening housing for the four-million Athenians, who continue to live in polykatoikias in need of urgent restoration in both their interior and exterior.

35 sqm Micro-apartment by Oikonomakis Siampakoulis architects, Athens, Greece

So, what happens next? In a city that has been dominated by such a strong architectural typology, how can contemporary architects push this identity forward, tackling present-day challenges while preserving all the positive aspects of the polykatoikia? Projects with green balconies and roofs, sustainable cladding materials and designs that strive for an A+ ranking in energy efficiency are slowly improving the urban fabric. Some architects also claim that certain demolition works are unavoidable to free up space for planting and public use. Throughout this article, the actual architecture of the polykatoikia is not discussed but rather its wider social, political, economic and environmental implications. True, its simple, clean, modernist form is perhaps what allowed it to multiply in such a fast pace. Still, the most important initiative for architects would be to collectively research, gather and respond to the 2024 needs of the Greek capital and I am positive that the evolution of the Athenian architectural identity will follow.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Top image: Marylinalcyonova, Building Density beneath Lycabettus Hill in Athens Greece 01, CC BY-SA 4.0

The post The Complicated Case of Polykatoikia, Athens’ Famous Postwar Apartment Blocks appeared first on Journal.

I have often wondered why more neighborhoods in America don’t have this unpretentious, egalitarian feel to them. Am I just picking up on a vacation vibe? Or is there something in the neighborhood’s history that has allowed it to remain an oasis of tiny houses in a state known for McMansions?

I have often wondered why more neighborhoods in America don’t have this unpretentious, egalitarian feel to them. Am I just picking up on a vacation vibe? Or is there something in the neighborhood’s history that has allowed it to remain an oasis of tiny houses in a state known for McMansions? For $2,095, a family could purchase one of these 420-square-foot (40-square-meter) houses on cement slabs. These homes were basic: no heat, no insulation and no air-conditioning. “For showers,” Staab explains, “there was a tin bucket on the roof to collect rainwater that, weather permitting, would be heated by the sun. If a buyer wanted to splurge, a water heater cost $6.”

For $2,095, a family could purchase one of these 420-square-foot (40-square-meter) houses on cement slabs. These homes were basic: no heat, no insulation and no air-conditioning. “For showers,” Staab explains, “there was a tin bucket on the roof to collect rainwater that, weather permitting, would be heated by the sun. If a buyer wanted to splurge, a water heater cost $6.” While many Ocean Beach III residents speak of the neighborhood as a throwback to the 1950s, a “simpler” time, I think of it as futuristic. In the 1950s, as people moved from tenements out to the suburbs, the trend was upsizing. More land, more space, and — for some people — even an extra little cottage out near the shore. This was the American Dream and, from the standpoint of the time, it had nothing to do with simplicity.

While many Ocean Beach III residents speak of the neighborhood as a throwback to the 1950s, a “simpler” time, I think of it as futuristic. In the 1950s, as people moved from tenements out to the suburbs, the trend was upsizing. More land, more space, and — for some people — even an extra little cottage out near the shore. This was the American Dream and, from the standpoint of the time, it had nothing to do with simplicity.